Two hundred and fifty years have passed since the American Revolution.

Although we mostly relate this important period in history to the famous year–1776– 1775 is the more appropriate year to begin acknowledging this celebration. That is because, many highly important events, enabling the war to commence, happened before the year formal events linked to war were initiated.

One might even argue that the Revolution had events that took place in 1774 as well (in fact it did), leading next to public controversies and ultimately the official signing of documents linked to our desires for independency. But like most points of time in history, we try to assign a specific date to the true commencement of an event as serious and important as a war, and try to define the events and time(s) when these events made this important time in history, undeniable and unforgettable.

Ten to fifteen years ago, I did much of my writing on the Revolutionary War and Colonial New York history for this blog devoted to the findings I made over the years, decades prior. And I admit, since then, I have done little to “update” these essays for the moment. Why? That is because these findings made since these initial 2009 to 2012 posts, have been quite extensive, and were worked out extensively on my two facebook pages. Those essays perhaps outshine the initial ones I developed pre-2015. Their type, and the amount of work done as these discoveries were being posted, were much more detailed and lengthier that the previous posts resulting from my work completed one the two decades before.

Why such large amounts all of a sudden appearing during this time? It is due to the world wide web, and Europe’s reaction to this new information technology. The United States educational programs were slow and resistant to sharing whatever “knowledge” they felt they “owned”. As usual, financial compensations were then required in order to learn. History was not available to the masses, so long as inquirers never tried to search the world wide web. Fortunately, a lot of these limiters are now reduced a lot.

In 1990, you had to have a PhD and the money needed to access rare documents at such special collections as those at Yale or Harvard libraries. Fortunately, Google was making an effort to having many of these documents scanned, to be made available for the world to see. But the scanning, preparation and finally release of such rare documents was a slow experience indeed. The delay of teaching the world, in a way that Google Books could accomplish, too ten to fifteen years to evolve into what it is now. As a result, knowing what I needed to see, and where to look, and how to translate these important papers, was hindered only by their availability or not on the internet.

The opening of the world libraries made it possible for me to answer questions that remained unanswered in local history for a good fifty to one hundred years. Regarding my study of colonial medicine in Hudson Valley, New York, the most important events that ensued due to references that became available on the internet were as follows:

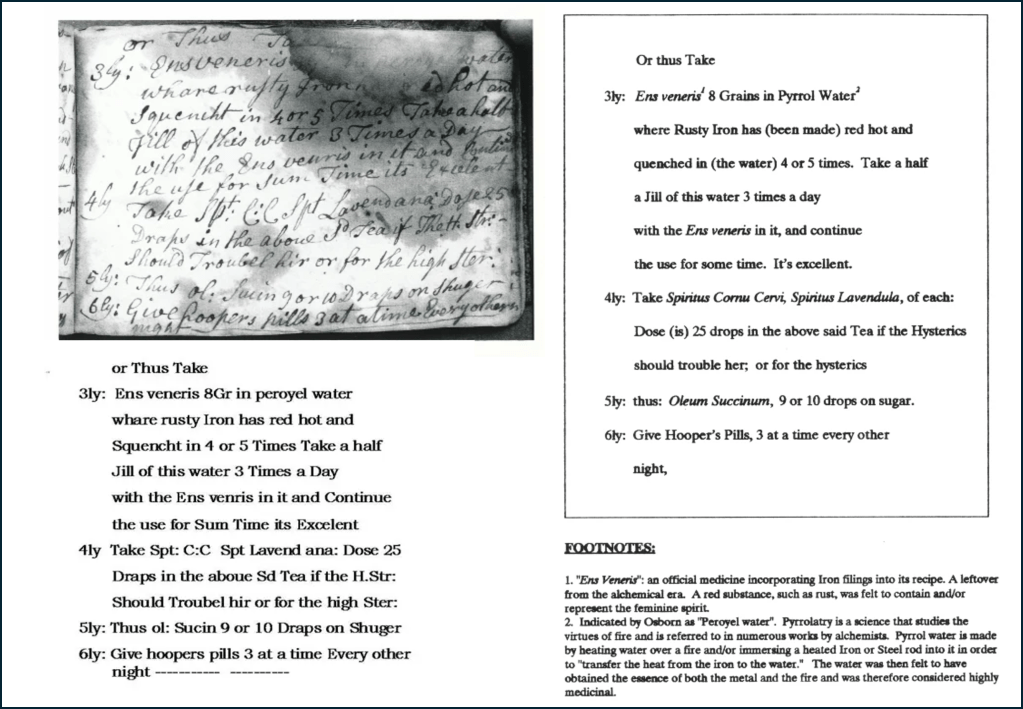

First, the discovery of George Starkey/Stirk and his work at Harvard University very early in colonial history, on the alchemical principles of what is popularly referred to as the “philosopher’s stone”, the prima vitae or essence of life, and its relationship with two medical recipes or ingredients referred to by Dr. Cornelius Osborn: ens veneris and sal ammoniac.

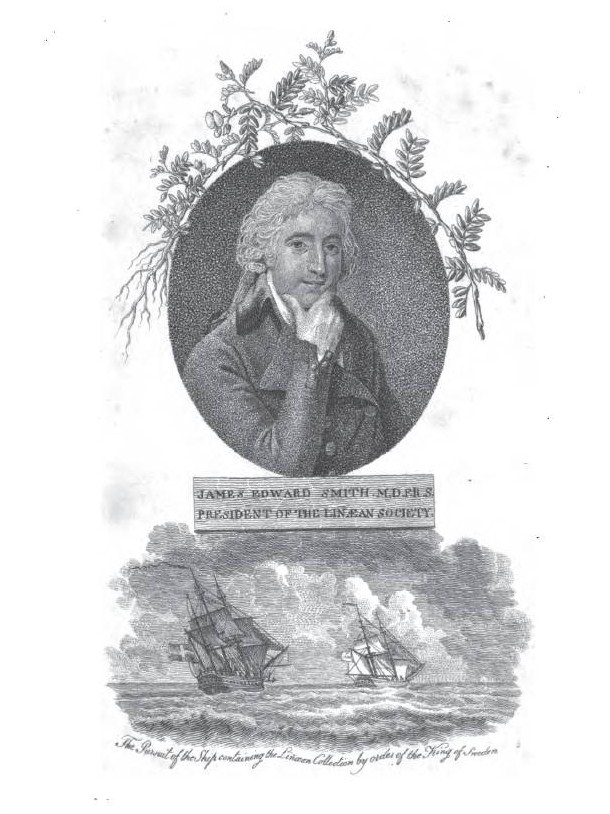

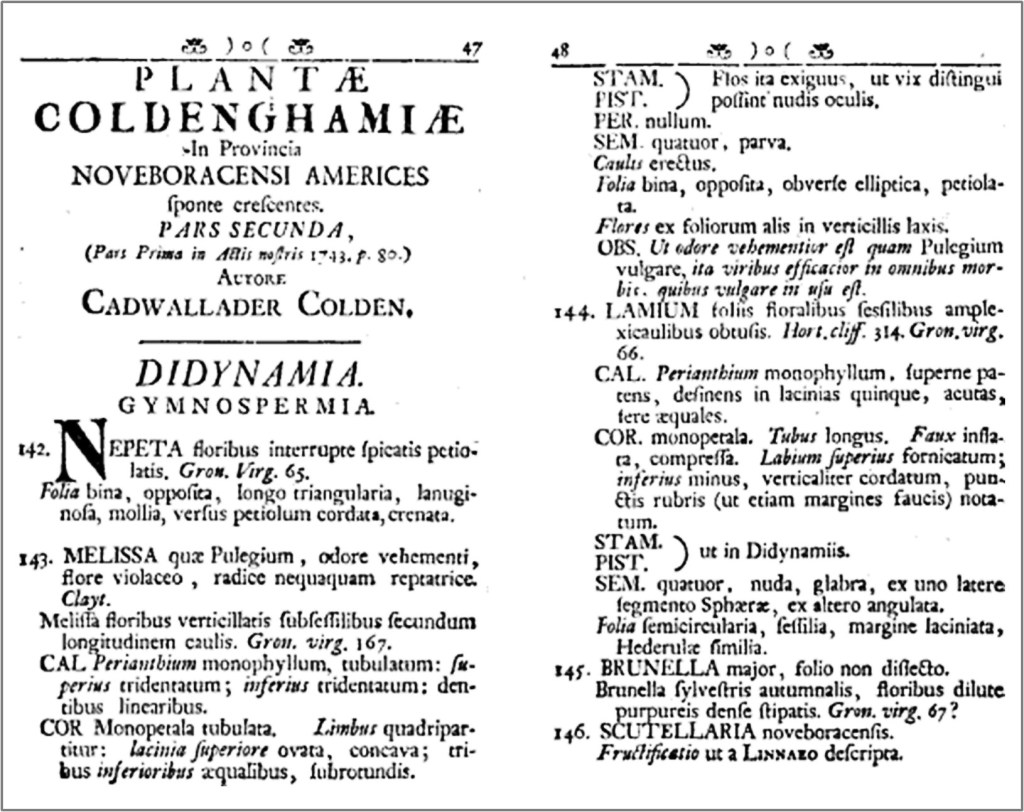

Second, the actual publication of Cadwallader Colden’s work on the Flora of Coldengham, New York. This was the first such documentation done on New York flora, and revealed important natural history observations by the author on the origins of some or the earliest introduced plants in this region. This was later complemented discovery of Jane Colden’s work by Hessian botanists and Carl Linne beginning about 1787, its rediscovery by Anglican scientists when the Linnaean collection was bought by England from Sweden in 1800, and again when the local Orange-Dutchess County Floral society rediscovered her work and finally reviewed int in manuscript form in the late 1950s.

Third, details on the life history of the first local physicians, in particular, examples of writings penned and published by such local physicians previous unresearched like . . .

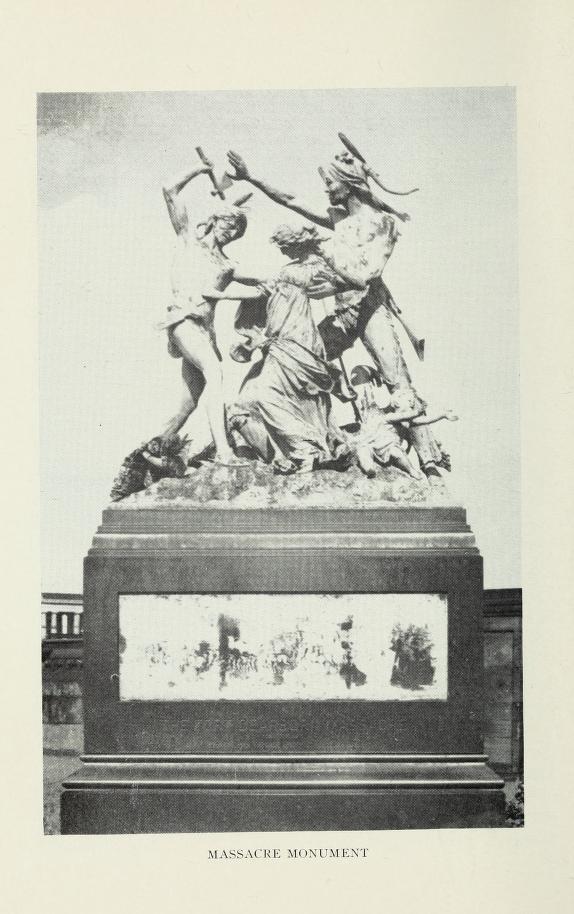

a) Isaac Vale Van Voorhis, who was forgotten because of his death as the third physician ever residing at Fort Dearborn Chicago during its first year of settlement. Dr. Van Voorhis experienced an unfortunate outcome due to his experience at the fort. He was one of the first graduates of Columbia University, the third from Columbia who served at Fort Dearborn, but the only one from Fishkill who was there at the worst of times. As a result, he was massacred during the initial hours of the War of 1812. His corpse not recovered for years. Due to his mistreatment by later individuals during the first major national recognition of this historical event, the descendants of other military leaders in this battle, trying to promote their relatives as “heroes” (some may in fact were not), retold some very personal talaes of what happened during the famous “Chicago massacre”. One in fact restated her family’s claim that the doctor was ‘cowardly’, when in fact he was trying to escort about 40 mothers and children from the center of the attack about to be made by Indians. These comments have since been interpreted by historians as demeaning and slanderish, but have since been remained as the versions retold by popular press writings published in fictional books, mostly for kids, providing half-truthful culture remembrances of this encounter. As a result, it has difficult to nearly impossible for historians to bring back the true story of who Dr. Van Voorhis was, his reason for servicing at the fort, and the many misfortunes he seemed to face to sign up to serve there, to obtain the recognition her earned at Columbia for earning his MD degree, for receiving the appropriate respect and recognition he needed as a very young soldier killed in a massacre. (In the image below, Dr. Van Voorhis is resting on the ground, beneath the 3 still standing in the re-rendering of this encounter produce by a famous sculpture, for site recognition day in the late 1800s; it is an object since removed from the site, ca. 1976, due to claims that it portrays the Native American aspect of this encounter in a “negative way.”)

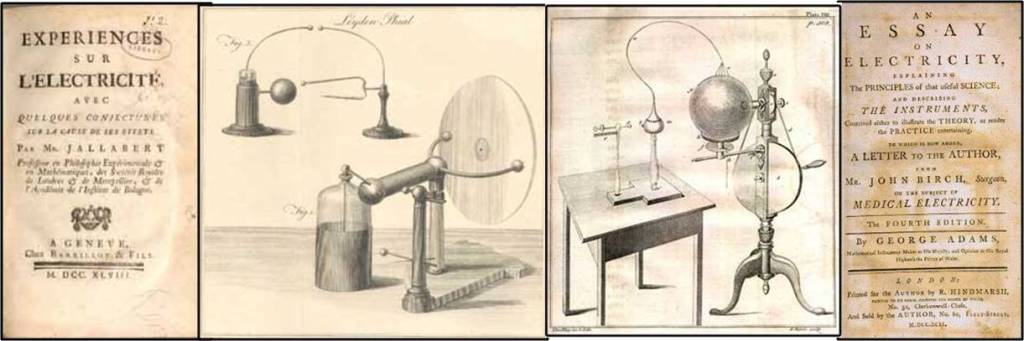

b) the local Dutch and Quaker histories related to the popularization and public acceptance of electric healing” in two forms–the copper-iron dielectric galvanic device theory that was born just across the border in Connecticut about 1795 but promoted by residents in the Quaker hamlet of Oswego Village, and the static electric generating flat disk therapy popularized by a Quaker removed living in Dover (Jedediah Tallman) and his follower who healed using bimetal calipers in “Fishkill” (now East Fishkill area). Still, the most intriguing part of this historical tale is the reason why and how a religion like Reformed Quakerism might take on the idea that “electricity” can be used to heal, perhaps even as a sign of “god” to them, which they envisioned and verbalized using the terms “force” and “universal energy.” Now, this isn’t the first time we were “electrified” in the Hudson Valley by the notion of God’s energetic “spirits”. The famous Leyden Jar came to the valley decades earlier, during the periods of Dutch family dominance and even “rule” between 1650 and 1690, with the possession and use of perfected Leyden Jars in this region evidenced by belongings documented in historical records, property belongings penned once the English had taken over New Netherlands, including upper Hudson Valley, in the very early 1700s.

c) Quaker/Quaker Reformed Doctor, Shadrach Ricketson, was famous for arguing that Poppy could be grown and cultivated in North America. And he introduced the cow pox vaccination technique to this country around 1802/1803. His famous book, published in 1806, served as a furthering of the work on home health, domestic medicine, healthy living practices ideology, the most widely respected version of which had, until this time, been penned by an English physician, well known for his unique entrepreneural, upper class, “well-endowed”, well-fed (meat and fat, gout-stricken), morbid obesity appearance (400 lbs or more) by the mid 1700s. Many contemporary book dealers in the U.S. homnor Shadrach as the first U.S. author to support the role of sports, recreation (indoor and outdoor), and athleticism on personal healthiness; to them, Ricketsons book on how to live healthy and stay in good health, is the first medical book written and printed by an American printer and press.

d) Poughkeepsie’s most important role in the popularization and dissemination of Thomsonian medicine philosophy and knowledge today considered the knowledge and popularizations of various forms of alternative medicine. The Poughkeepsie printing press made it possible for the preachings of Thomsonism to be printed and dispersed across this region. This press even remained one of the most important in the history of this “non-allopathic” medical profession by the late 1830s; and remained one of the most important, and finally the only printer of this discipline for northeastern U.S., by the mid 1840s. By the late 1840s, this discipline broadened its versions of medical practice and related fields of interest greatly, and nearly every practice of healing ignored by regular doctors, was taken on and preached by this rapidly growing “reformed medicine” school of thought. By 1850, the Orson Fowler family, promoted how to build the healthy octagon home, and how to practice a very useful form of human psychological diagnosis and treatment known as phrenology, and used their octagon house and local public speaking places to promote these ideologies. Such places allowed Mary Baker Eddyism, Quimbyism, Herbal Medicine preachings, Shakerism, Indian Root Doctoring, Water Cure or hydropathy, Sylvester Graham’s early Vegetarianism like movement, Mountain/Climate/Fresh Air cures, wearing Galvanic Coins and Necklaces, Andrew Jackson Davis’s teachings in Seancing, to become important parts of our local culture. There is but one profession they did miss however, which had much the same preachings–Hahnemannism, introduced by the nearby German communities in Allentown area Pennsylvania. They came to this region by way of the regular doctors, Dr. Vanderbilt for one, convinced this was a valid, useful preaching or teaching.

e) the development of the medical profession and its teachings from what it was during the early Colonial Period and early Revolutionary War era, to how the State medical associations were formed and their constant changes in education, learning and requirements from the end of the war until this profession became more solidified by the 1820s, the first official medical society meetings, the educational experiences, the discoveries, and the first medical writings of local physicians were documented in their quarterly trade journal for this region.

A total family life medical professions study of Dr. Cornelius Osborn (1722/3 – 1782) demonstrates most of the stages of legal development of the profession. Dr. Osborn himself was trained using Apothecary Guild licensing practices carried out in Europe (England), but probably as a resident of the lower Orange County region near Haverstraw. Evidence suggesting this is the fact that a known highly trained practitioner with the Osborn surname is noted in this area, along with at least some related families. In the Haverstraw churches baptismal records, a Cornelius Osborn is found baptized for 1722; a note made about Cors. Osborn by Benson Lossing gives a date, from interviewing family members in the early 1800s, that is one year off. The father of Cors. is named James. His responsibility around 1720 was surveying the region in preparation for building new roads leading to Ulster County to the north, the southern boundary of which then was just north of what is now the northern edge of Newburgh (by Route 84). Just west of this area was the land upon which Cadwallader Colden settled.

Adjacent to the Osborns in Haverstraw area was, just off the Hudson River in Florida, NY, was a family, into the household or which a young boy named David Wood would be transferred by his much larger extended family of Methodists, who lived in the Flushing area to the southeast, and across the Hudson River directly to the east. About 20 years later, David Wood learned medicine taught to him by a German family residing down near Warwick. During his apprentice years, David Wood was trained by three or four specialists–someone practiced in medicine, another individual learned in apothecary (possibly from across the border in what is now New Jersey), a doctor practicing husbandry and the practice of animal health, and finally, from a male midwife. These are all detailed in a book on the teachings Wood went through during this time.

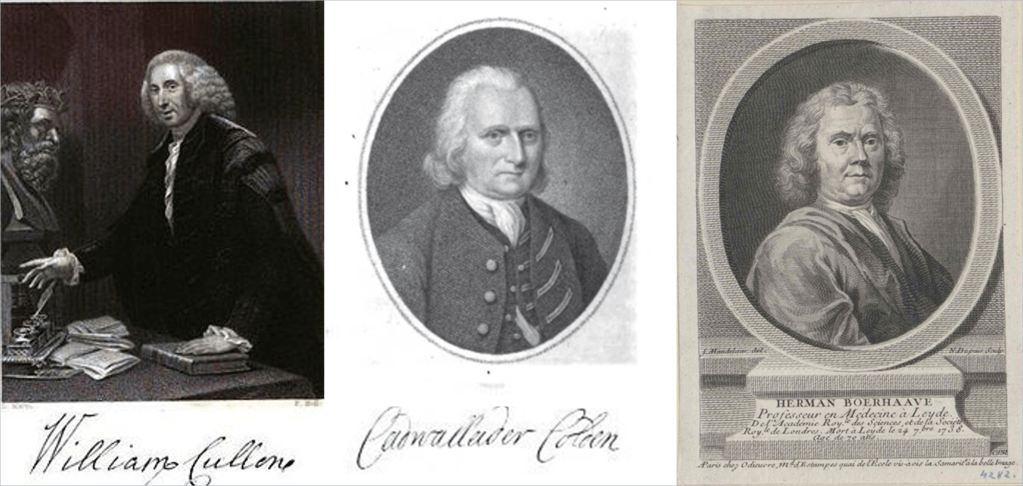

Then there was the training of Cadwallader Colden, at the northern end of Orange County, the southern edge of Ulster County. Cad Colden was trained by a physicians’ business in London, about 1707-1710. He received his pre-medical college education from University of Edinburgh, during the three years before.

The doctors of the Hudson Valley learned medicine in various ways. Important to note here is the fact that many if not most practitioners were well trained and learned in medicine, more than there were self-proclaimed, untrained “healers.” The bait of medical historians is to frequently preach the notion that educated physicians were rare in the early Colonies, which is only right if you take a one-sided, biased look at the profession during this period in local history. Such a claim was made forever popular when it was claimed by the British writer detailing New York Colonial history, Philip Smith, ca 1750. However, his writing on New York history and the education of New York residents was solely British in nature, and the British were indeed in political and intellectual competition with the Dutch throughout the decade prior. They won an important part of this political “war”, characterized as a series of political skirmishes on different claims and subjects, as the British successfully, finally managed to take New York back from the Dutch–twice. The survival of Smith’s state left subsequent researchers and writers on local medical history robbed of nearly all of the history and Dutch based truths about this region. Dutch settlers history demonstrates a very large number of settlers and travelers through this region who were in fact well educated and referred to as “doctors”. Perhaps as many as 25% of these earlier Dutch patrons passing through this region were trained esquires, and religious leaders, politicians, historians, educated in the classic writings, multilinguistic, engineers, mathematicians, philosophers, and physicians. Such was nature of the advanced education programs situated throughout eastern, middle and western Europe. British writer Philip Smith was never interested in this fact about their levels of education.

So how learned was Dr. Cornelius Osborn when he was recommended by Col. Abraham Swartwout to be recruited, to serve the Fishkill regiment led by Swartwout, with his son James to serve as his Field Physician assistant?.

Osborn was granted official acceptance of his medical ideology by Samuel Bard just before the war began, in August 1775. In spite of his probably apothecarian-chymistry focused training, he was very fit for this work, and he was a fairly well trained chemist of numerous uses to the troops as well as their leaders. But he was also trained as a combined practical/philosophical chemist (“new apothecare”). Did Bard ever know this about Dr. Cors. Osborn?

This leads up to how his sons got trained to become doctors; two out of three (James and Thomas) were fully accepted as such.

His oldest son James, earned his MD through approval after the war; he was his father’s assistant during the War, probably approved as an MD by a local esquire or government leader, ca. 1784. He even left us a manuscript, mimicking (copying) his father’s for the most part, for the written materials required for his licensure (to prove his ability to write).

The middle son Peter was less fortunate. The Dutchess County Medical Society was forming and regularly meeting by the time Peter was old enough. The society defined the requirements for teaching, testing and approving those who earned their licenses in medicine. Until then, one learned by being trained by another physician and/or by serving as an assistant to the surgeon for a military regiment. Peter attempted to latter. Peter probably hoped this process would be as easy for him, as repeating the his father’s work was for James. That wasn’t the case. “Medicine” then, was not just practicing your skills in apothecary science, making concoctions of medicines and such. And so after his first 3 years of service, attempting to assist the military surgeon, Peter was required to repeat his position again after 3 years, which he declined, and so never became a physician.

The youngest son of Cornelius Osborn was Thomson. By the time Thomson was old enough to qualify for medical training, another increasingly famous physician Bartow White had moved to Fishkill. Dr. Bartow White was the son of Dr. Ebenezer White of Westchester, who also served in the Revolution like Dr. Cornelius Osborn. Ebenezer sent his son to the young medical school in New York City–Columbia, just before they made classes a requirement for obtaining your license. Whether or not Thomas went to Columbia is uncertain, and it seems likely he didn’t. Instead, Bartow may have held classes at his home, for Thomas Osborn is noted as learning alongside Dr. Bartow White. Dr White was responsible for licensing about two or more other young men per year in medicine between 1797 and 1805. (One of the better known was Dr. Isaac Van Voorhis who died in Chicago is one of them. Dr. Van Voorhis wrote and had published an article on his experience next to Dr. White, performing a forensic surgery investigation of a patient’s body.)

Thomas, Peter and James Osborn had a nephew, Cornelius Remsen, who moved in with them after the Revolution. Cornelius Remsen was born in the hamlet of Newton, today, an unknown, unrecognized hamlet located next to Livingston Manor in the Catskills. In past attempts to document Cors. Remsen’s history, all past history and family genealogy writers misidentified his birth place as Newton, “Long Island”, interpreted as Newtown. Reviewing the records of Newtown, Long Island, there were members of the Remsen family there, with a family history published stating this name actually came from a prior surname.

According to early family interviews performed by the most famous post-Revolution history writer, Benson Lossing, he penned “Newton, LI” as the birthplace. But, a review of historical papers and ephemera led me to uncover the phrase “Newton, Liv[ingston] as also the place of a mercantile store in New York, which ended up being where Cors. Remsen was raised. Also in this hamlet there was the Du Bois family, who owned a mercantile business there. They referred to their business address as being in Newton. This was about the time state congressman Samuel Mitchell wrote and had passed an act requiring that plans be made to name all areas that fit the definition of areas considered well populated hamlets. Cors. Osborn’s past business ventures, such as lending mortgages, happened to occur in this same region

At the Osborn family residence, Cornelius Remsen resided in the house located at the Baxtertown Road-Osborn Hill Rd intersection. He became the first Osborn family member to learn fully under Dr. Bartow White, without attending classes at Columbia medical school. He became an MD without necessarily having to travel to NYC for his formal classroom lectures and science training, and served in the War of 1812 right after his licensure as an MD. He is also linked to the importance of Baxtertown in local slave remission history, for he was a major landowner and contributor to the development of the Zionist church raised in the village of Wappingers. His daughters never married and had children.

Interestingly, I learned most of the above by going through books and other printed items–manuscripts, microfilm, etc.. All of these documents required visits to the libraries that held them, in New York City, Poughkeepsie, Goshen, Washingtonville, ad nauseum, during the 25 years prior. Once the internet became a possibility, in some ways, the outcomes of my searched improved; but that did take me almost 20 years to reach the state we are now in. Original documents from the genealogical libraries, still cannot be duplicated as well, unfortunately.

During this review of medical documents, articles and the like published during the post-Revolutionary War years, the outbreak of Yellow Fever during this time led to the first production of disease maps in United States history by Valentine Seaman of Yonkers-upper Manhattan area, demonstrating the roles of human population features, local commercial practices, natural ecology, and weather-climate-topographic requirements, for epidemic to happen, and in some places, endemic disease patterns to develop.

Due to the availability of journals and popular magazines globally by about 2005, I was able to find and analyze dozens of the first disease maps and for the first time document the detailed history and philosophy of medical geography, and spatial epidemiology as a specialty, being published in this field for several of my discoveries and related writings, starting with my MS thesis in 2000, becoming known as a historical medical geographer/epidemiologist for the first time following the publication of my international commentary article about John Snow’s disease mapping and the U.S. produce soil geochemistry map depicting how the environment influences epidemic patterns in the midwest, published by a medical epidemiological journal from England around 2009.

The best example of how I used these research experiences to build upon the knowledge of local medical history for the first time since about 1910, came with my publication of Dr. Cornelius Osborn’s history and his manuscript written in 1763 by the Dutchess County Historical Society, in their Yearbook for the year 1990. But that research was penned during the non-internet years. Once I commenced the use of internet resources around 1992, it took me another five years to begin to find the historical documents needed to engage in a thorough nationwide research on this topic.

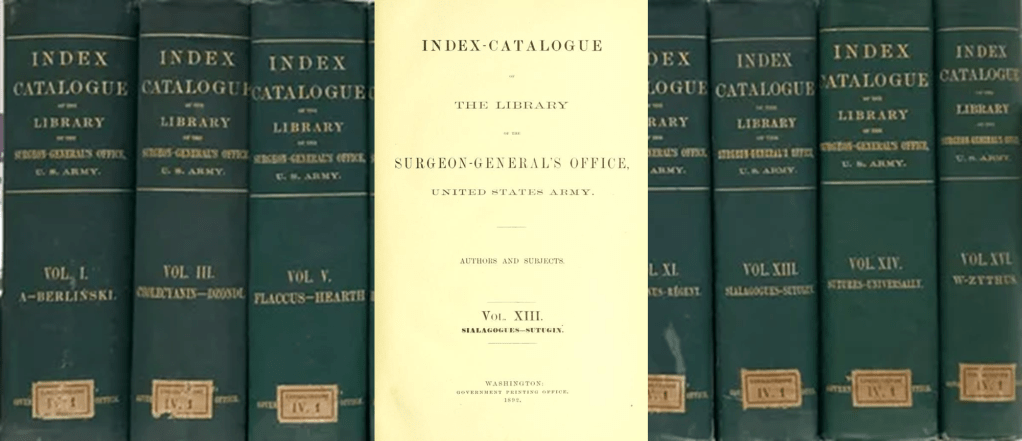

My most important resource then was the series of book documenting the holdings (“Catalogue”) of the Surgeon General’s library in Washington DC, a 35 volume (one per year, A-Z in sequence per printing) encyclopediac set of all materials perhaps ever published on medicine. I spent 3 to 5 years reviewing this set and used this reference to order more than 5000 articles out of my University Library (Portland State University), during my years as a graduate student there–1996 to 1998. I received about 50% of these requests.

The use of this Catalogue also enabled me to review all of the local Hudson Valley, New York physicians of the past, and the books they would have been read in. This resulted in my ability to locate and research many of our local physician’s references, but especially see whom in New York was published, by state, county, town, surname, school, professional agencies, key topics (outbreaks) there were experienced in and the related activities they were engaged in. Dr. Osborn was not found in this series, although the chief authors he was read in were. Dr Cadwallader Colden was thoroughly covered in this important series of references.

As a result, I was able to locate and save on my personal computer much of the work of Dr. Colden. Almost nothing was written about his daughter Jane Colden, but plenty was available on the earliest natural history writings penned by associates of the Coldens in the field of botany and natural history, and in particular, writings by later botanists who made reference to these initial discoverers of the local medical plants.

Up until this time, the only version I could review on Colden’s work on colonial New York flora was reprinted, but untranslated, by the New York Botanical Garden. But viewing those documents was at the time not allowed, except for scholastic purposes, in the form of enrollment in a PhD program. The availability of Colden’s work on the internet by the late 2000s, made my research on this document possible, without need to spend time travelling during a sabbatical. I therefore was able to engage in the bulk of this work on the Coldenghamia Flora, was from about 2009 to present. My first translation of Colden’s two part article from Latin was completed in 2010, the second by 2012, with Jane Colden’s history added to this work later that year.

Thus, one of the most important outcomes of this work is/was my ability to translate and add knowledge to the very first publication of the Flora of New York, by Cadwallader Colden. It was submitted by Gov. Colden to one or more of his “associates” in natural science, leading to its hand to hand transfer across botanists, until it reached the desk of Carl von Linne. Over the next two years, it was transformed and readied for publication by Linne, and became a formal written scientific document, published in two parts, the last portion published 1751. This represented the synopsis of work Cadwallader, and his daughter Jane had done, between about 1738 and 1745.

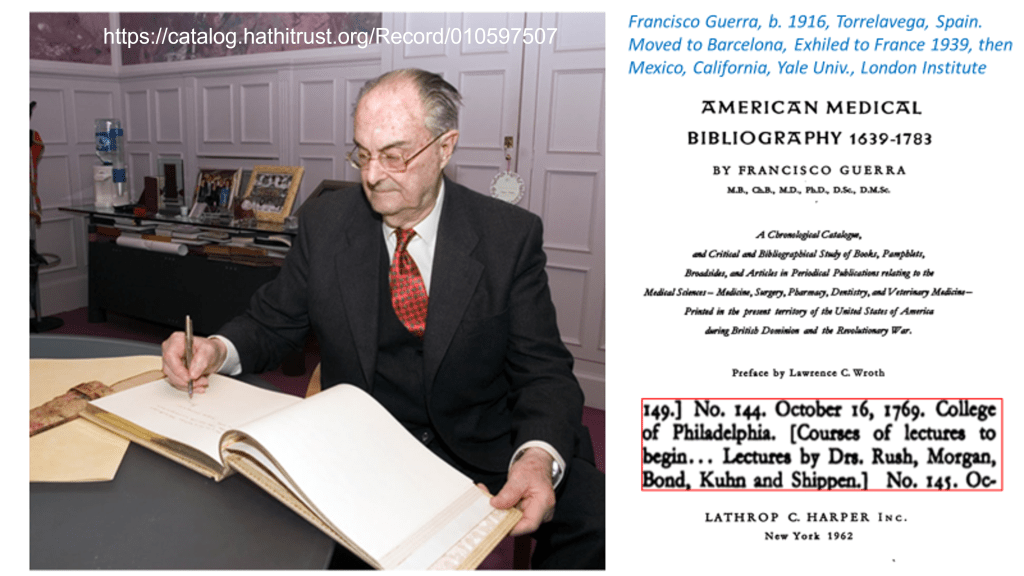

Another highly important discovery I made while researching Colonial to Revolutionary War medicine on the internet, was my review of some work engaged in by an underappreciated history of medicine scholar: Dr. Francisca Guerra. His writings in the history of Medicine were in Spanish, but he was forced to leave Spain due to political problems in the mid 1900s, and so removed first to parts of Western Europe, then South America and Mexico where he served as professor in medicine and history, and later transferred to the US where became an emeritus professor and history of medicine expert for Yale for his latter years. It was during that stay at Yale, that he catalogued the entire newspaper collection of the colonial to early post-colonial U.S. years, focusing upon anything that dealt with health and medicine published mostly as advertising, medical orders, announcements, notices to potential students, ad infinitum. This end product also had photographic replications of the majority of these ads and notices. This document alone takes a researcher at least a month to thorough review, for your colony, province and state. It provides the most widespread details on the practice and learning of medicine for this time. Its lack of review by most history of medicine researchers these past 30 years, is why many of the common myths about medicine and colonial doctors, at the time the War began, are repeatedly misstated in the majority of articles and descriptive writings produced about later Colonial-Revolutionary War medicine, with a focus on the practices of Bard, Rush, etc. Much of what historians need to know about Revolutionary War medicine, has never been shared, and what is or has been shared, remains very Anglocentric.

Being published so early in our local history, it was in numerous ways the first event detailing numerous things about North American and New York History. It was not only the first “flora” of this region published, it also documented some malingering early introduced species in the Hudson Valley, New York, local plant history and ecology details, never fully researched or reviewed by botanists to date.

This document, ultimately being linked to the work of daughter Jane Colden as well, was the first to express certain local human culture aspects of local ecology and anthropology features. Jane herself coined the term “Hudsonian” in her work, to describe the unique locally defined habits people living here had taken on, to incorporate the local herbs, edible plants parts, and the like, into their normal living routine. The documentation of ethnobotany for our region was thus fully accomplished by Cad Colden, through his 1735 and 1745 works on the Iroquois and their way of living and surviving as a body of people, and through Jane’s manuscript notes kept in her journal and early plant drawings developed, to accompany her observations and notes.

Both of these items, anyone learned in Colonial history, will probably be familiar with. For during the next century, as the United States first got formed, and then grew in size and complexity, most classes in the first colleges would note a lot of Colden’s work done in nearly every field they were teaching, including politics, the art of war, American Indians, farming and agriculture, anthropology, linguistics, paleontology, geology, economy, morals and human rights, botany, astronomy, climate, epidemiology, diseases, epidemics, and health. Cadwallader Colden’s name is mentioned literally in hundreds of items published between 1750 and 1850 on these topics.

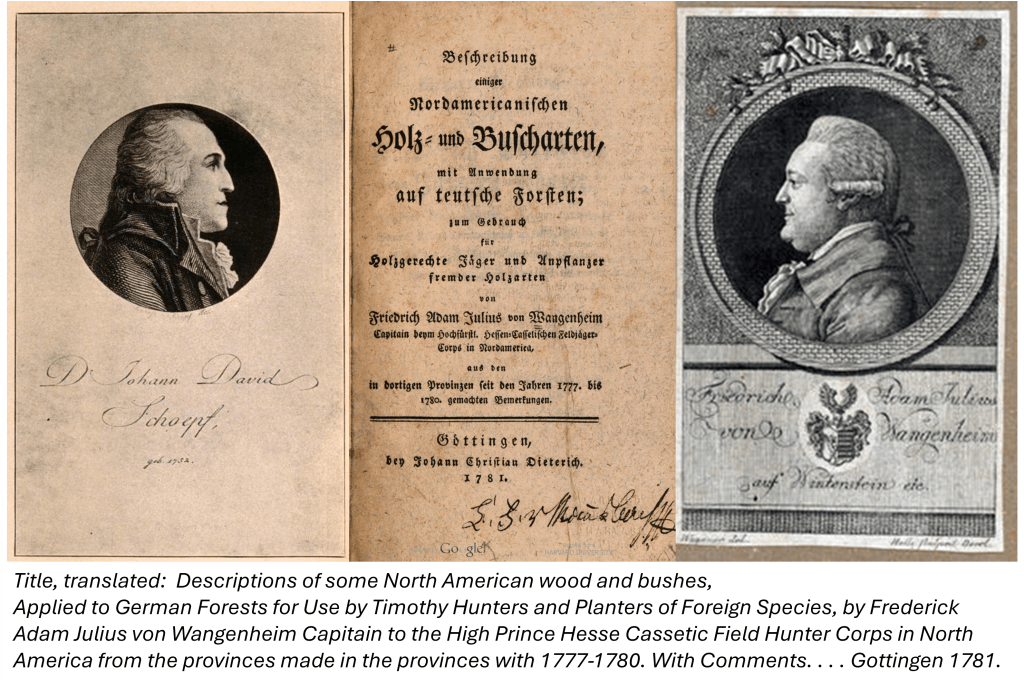

The work of his daughter was lost for a short while, for it never led to an initial publication due to her marriage soon after this work was minished, and her fairly early death just a decade after much of her combined ethnobotany-scientific botany was completed. The notes she had kept left this country completely at the end of the Revolution, about 1783, when her papers were handed over to a young Hessian military leader, scientist, naturalist, military landscape artist, and engineer just before the British Army gave up Manhattan Island. Her papers remained dormant in the place where this professor later developed the field of Forestry as a college or university level ‘natural philosophy’ (science). Their rediscovery in his later years, led to the immediate publication of her work and the development of her recognition by middle European schools and scientists, well before the British natural scientists began to honor her accomplishments.

Interestingly, like Cadwallader Colden’s work on New York Flora, that work (the work of Jane and that forester) remained untranslated, untranscribed for a century, then forgotten in western European science history, then lost and misplaced in the U.S. Ivy league libraries, then Jane’s work was finally rediscovered by the local Garden Club, 1950s; a portion of her accomplishments, in English, reprinted. Any related work penned in German, may have been printed by the Hessians, but never honored and translated for use by Anglican colleges and universities. Ethnocentricity robbed many scientists the rights to see, learn from, and know, the discoveries made by the scientists over there in Eastern Europe.

In 2024, I successfully translated into English the important work by the Hessian scholar, scientist, botanist, military leader, and economic forester, originally published in old German.

In terms of accomplishments, the above are worth noting. But the opening of the Worldwide Catalogues also made it possible for me to successfully finalize my work on the kinds of medicine that were practices about the colony, province and later State of New York, and the same for physicians uncovered who also left us with important writings discovered how and what they learned. This provided individuals into the history of pharmacy, medicine, science, a chance for the first time to understand in much more detail the way people became doctors in the early Colonies/U.S., and the many ways they were taught and learned.

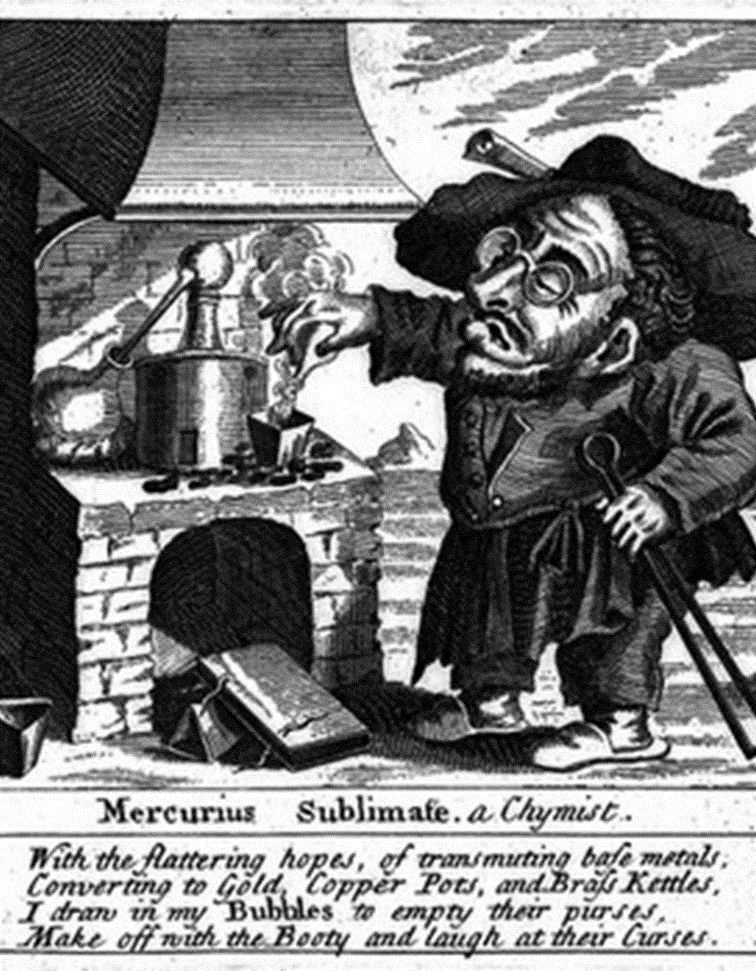

History has this habit of categorizing the history of medicine, by the use of terms like quacks versus physicians. Yet the quacks referred to in the 1750 History of New York book, which is the key reason and source for this ever-important sterotyping of doctors, be they ‘trained” or ‘untrained” based upon some ethnocentric ideology, remains the way modern historians teach the history of medicine. They teach their students there is a “right” and a “wrong” way to practice per period in history, an educated versus uneducated version, an official versus non-official way.

Yet, the truth here is best stated as — there is a method taught by actively practicing clinical groups, another taught by the theorists, philosophers and academicians as taught in the classroom, another taught by the former barber, now chirurgeon who is an expert in physiology, anatomy, and cutting and displaying the human body, and still another type of doctor belonging to the apothecary guild who was taught much the same by books, but also who learned the new science–chemistry–of life, animals, drugs, and was scientifically trained and experienced and perhaps only a few steps more than the chymist who became famous because he successfully treated a member of royalty with some unusual potion or magnetic balm or unexplainable fever-breaking bark found on some distant continent. No doctor, from any of these lines of specialty, was smarter or greatly better than the others. All became popular, due to their accomplishments, especially those displaying less failures when treating the most ill of patients.

The manuscript I reviewed on our local physician Dr. Cornelius Osborn can now be almost fully explained. It is just an 82 page handwritten document. But it has the materia medica, the ways of experimenting and producing medicine, the ways of giving that medicine the potency it needs, the way to energize it naturally, or through the assistance of some higher power–these all are in his writings, and can only be understood, by reading as much as possible about all the possible believe for that time that he practiced (1735-1782), and understand the teaching of the multiple kinds of doctoring for several generations before him. Medical philosophy changed back then, quite extensively, every few (7-12) years.

So, in prep for the 250th, there are two items I have not yet fully thought through. The first is, medicine at the dawn of the revolution is vastly different than that practiced at the end. And there are two other periods–one or two years before–and one or two years after–when ideas were also very different, about to undergo change and solidification. Five to seven years after the Revolution, medicine was in its new form in the United States. To some it was trying to add to the British ideology; but to many anti-Anglican families, a new patriotic ideology was emerging, based on the idea that the US has different diseases unlike those of Europe, because the US, its weather, its climate, its Geology, its Paleontology are different. Disease was then thought to be largely a product of nature, and individual family traits or health related histories. Places were so different than each other, that certain places effectively treated or provided the medicines needed for where the ailing person lived, and whether or not that individual could acculturate or not. This ideology did not exist in the same way before the Revolution. The Revolutionary War, and the sharing of medical teachings during the war, between doctors from different countries working together (on both sides), enables doctors to learn where they were performing better and where they had failed, based upon what the others just taught him.

The preachings about Revolutionary War medicine, will most likely take that classical and heavily prejudiced, mistaken approach to teaching, by discussion the notions of there being doctors practicing quackery or not, doctors who went to a European school or not, doctors who performed strange ideology like sweating or not (avoiding as much as possible the mention that nearly everyone bled at the time). Just as the war began in North America, Reformed Medicine was taught and existed in Middle Europe (Hungary). This Reformed medicine questioned the heavy preaching of certain traditions like blood letting–it didn’t condone it totally, only asked that physicians be more observants of when it did work versus did not.

These Reformed doctors did in fact also take on the old favorites learned from by physicians of all sorts–Thomas Sydenham. Sydenham relied upon clinical observations and experience, not just speculative theory, to make his recommendations–and these were all based upon the epidemics he worked in and through. Doctors of all sorts respected the works like those of Sydenham, and many also honored the classics still being published by Hippocrates and Galen. But they relied quite a bit on Anglican ideology over that of Hungarian ideology. Even though both were equally wrong and equally right, in major parts of their ideology. When the Revolutionary war began, our leader Samuel Bard favored the Anglican teachings, not the Middle European teachings. Thus, the famous William Cullen’s preachings of humours prevailed, as did that line of reasoning for why to bleed patients like we will, and should, not the preachings of Slavic-Hungarian writers, whose focus was on observations and experience in the hospital, like de Haec and Stollius.

The Forests of Harlem. The first forestry book – by Friedrich Adam Julius von Wangenheim.