A Small Pox Invasion

Les Canades, or the Canadians, are people who in the modern sense live in Canada. But Canada was not always called Canada and it Canadians were certainly not all called Canadians. “Canades” is a term created by Jacques Cartier, one of the earliest explorers of Canada, who learned of the Huron word kanata for village. Cartier used this term to refer to the area about the Hurons’ settlement, which at the time was somewhere near what is now Quebec City. A century later, this territory earned the name New France due to its predominantly French settlement patterns, most of which could be found along the St. Lawrence Seaway heading inland towards the Great Lakes.

As French explorers entered into North America, and made their way through the Canades settlements and from there over to the Great Lakes, the land they passed through also became a part of New France. Once the British regained control of these more inland parts of the continent, Quebec remained its own territory and the remaining lands referred to generally as Canada. This area known as Canada continued to increase in size as the explorers increased the size of this French claim, referring to lands west of the Great Lakes as Canada and lands extending southward from the Great Lakes along the Mississippi River towards Louisiana more sections of New France.

Dene, of the Dene Nation located just south of Great Slave Lake, on land agreed to by the Crown in the original Right of Canada

The Canades Cartier was referring to has more recently been referred to as Lower Crees. Some have been referred to them as Swampy Cree, a name suggesting many were residing in the lowlands. According to the philosophy of disease at the time of the Small Pox epidemic that made its way through this settlement and its neighbors from 1781 to 1785, the Lowlands was one of the least healthiest places to reside. The European philosophy for how such a disease could impact so many people as it did the Cree was based on impressions they had about the strength and stature of the Cree due to the way they lived. The disease could be brought in by weather, induced by climate, or caused by any of the many natural elements local to this environment felt to be coducive of disease. But the way in which this disease came into the region, the ability to trace its probable source and route, had many European and Euro-American physicians puzzled.

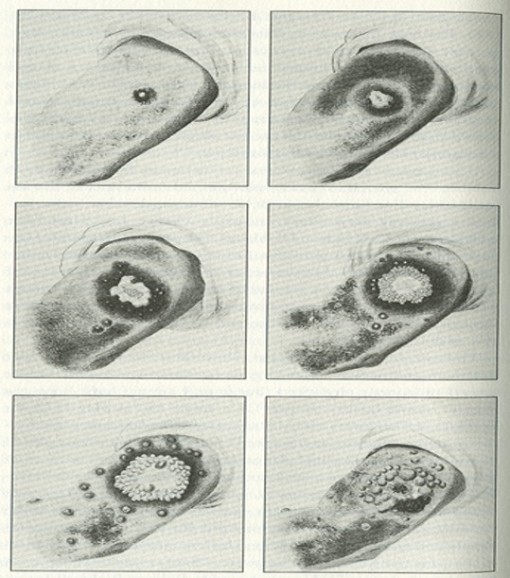

Aztec-Mayan Traditional Drawings also depicted Measles and Small Pox as a disease

Tracing the Diffusion of Small Pox

This disease has two possible routes it could have taken to the Cree.

Route 1 (yellow, red options): Beginning as far south as Mexico in 1779, small pox could have made its way across the continental proper and northward by taking the typical trade routes northward (yellow route, most widely accepted), or by passing across the prairie to Saskatchewan River (Arthur Ray’s theory, the red route). These routes involve Shoshone and Snake River (Paul Hackett) onto the Western Canadian Plains, and the Missouri River northward onto the Eastern Canadian Plains.

(Poor compression algorithm! Click on image to view)

Route 2 (orange): This disease came in by way of the South Saskatchewan River, and a little more from the west. Evidence for this is the fact that Shoshones were taken ill in the Red Deer River Valley, an epidemic which some Northern Ojibway (aka Bunjee or Lake Indians) warriors witnessed during their trip back to Cumberland House west of Lake Winnepeg. The Ojibway briefly made contact with the Shoshones on their way back home, noting the Shoshone to be quite ill. These Ojibway shared this story after arriving at Cumberland House several weeks later, in winter of 1781-2. This appears to be the most credible way in which small pox could have came upon Cree settlements.

.

One could say that as this disease began its path of diffusion eastward along the overland routes, that it pretty much followed the river banks making its way towards Lake Winnepeg. To remain in an infectious state, it had to travel mostly from person to person, cabin to cabin, encampment to encampment, tipi to tipi. At the time there were a number of Mandan villages situated along the South Saskatchewan. These Mandans had trade relations with other Native American groups south of the Canadian Border down in the Dakotas. Most of the Mandans and their partners resided on the Missouri River or one of its tributaries, such as the Red River. This trade facilitated the diffusion of small pox along these trade routes, So in due time, as the disease made its way eastward towards more settled parts of Canada, the numerous business establishments where Native Americans tended to aggregate assisted it in making its way along the path leading to Hudson Bay. For now (as of 10/2011) there is very little if any evidence suggesting an initial introduction of measles by way of any south to southeastern routes; the population requirements were there, but no documented introduction of measles from Toronto, the Great Lakes, or any of the many former New France settlements could be found.

A Cree Winter Camp, ca. 1930s

Once the final destination of this smoldering epidemic was reached, the shoreline of Hudson Bay, this disease stopped because it had reached the end of its routes geographically. Fortunately, the travel across Hudson Bay wasn’t able to spread the disease much beyond the immediate Cree settlements. Even the trip towards the relatively close Severn House, from both directions, seemed to be protected from this contagion.

From Victor P. Lytwyn. The Hurons referred to as Canades. see p. 169-170 for Lowland Cree discussion.

Arthur J. Ray. Indians in the Fur Trade: Their Role as Trappers, Hunters and Middlemen in the Lands Southwest of Hudson Bay. 1670-1870 . Toronto: University of Toronto Press 1974 . pp. 105-7.

E. J. Paul Hackett. A Very Remarkable Sickness: The Diffusion of Directly Transmitted, Acute Infections Diseases in the Petit Nord, 1670-1848. University of Manitoba. PhD Dissertation. 1999. p. 190.

The above is the distribution of small pox claims in electronic medical records from several years back. There are no outbreaks of small pox today, and these spots where the disease is noted in medical records could refer to history from another country, or rule outs, or mistaken entries.

The above is a small pox distribution map, noting where it was still prevailing in the mid-1950s.

The next map depicts a late 1800s review of Central American Geography, Anthropology and History as parts of a Historical Set on the Human Race. It is covered extensively on another page, at https://brianaltonenmph.com/gis/historical-disease-maps/centralmexico/

The distribution of Small Pox at higher elevation settings is linked to indigenous rural settings located in that region. A second focus for the disease was noted in the heart of Mexico just ssw of the Yucatan. The third is along the western face of Mexico facing the Pacific.

Ourvoices.ca – Omushkego Oral History Project

http://www.ourvoices.ca

Image of Father Emile Saindon with seven unidentified Cree boys. Archives Deschatelets. Fonds Saindon.

There were no vaccinations for much of the mission history. There was the practice of inoculations that commenced around 1795, but this practice in the Native setting, in particular by missionary physicians would take a decade or two to become established. By then, the cow pox option for small pox was the more common option. This image of what the measles, either in disease or inoculation form, might induce in the skin. By the early 1800s, it was known that certain periods in the infection were better to use than others for inoculating, which consisted mainly of a scratch the pox, and then pass this flesh and scales of infected epiderm that was removed to a scratch left on the skin of the receiving patient. (It would take a century to finally understand why the organism at a certain stage in this development process was most important.)

It is possible that cow pox may have been attempted early on with indigenous groups as well. But its entry into North America is late 18th century and even then was mostly by way of the mid-Atlantic region. Other Hudsons Bay routes may have been taken by individuals aware of this new preventive practice, making it possible for both measles inoculation and cow pox vaccination to diffuse inland in Canada along typical trade routes heading from New Brunswick towards Quebec. This is very different from the inland migration of the small pox by way of major water routes coming up from the south and southsouthwest. The geographic differences between these two diffusion/migration routes suggests that independent diffusion processes for infectious disease happened.

Cree students at the Anglican-run Lac la Ronge Mission School in Saskatchewan in 1945. (Archives and Library of Canada.) | Library and Archives of Canada. (Source: www.huffingtonpost.ca)

We can also assign a chronology to how the diseases migrated into Canadian Cree and other indigenous cultures based on this initial Cree event. In the sequence occupancy model, a late 19th century economic geography concept, there are a series of sociological development periods defined for an area. The indigenous groups are traditionally considered the first of the periods of growth that a part of the U.S. or North America undertakes as it is being settled. The cross-cultural events for each of these sequential states in rural/population growth and development will also demonstrate a certain lineage to the diseases as they infect a settlement that is new to cross-cultural interactions.

There are three important periods in sequent occupancy thinking and publication that are important to note.

The famous U.S. physician Benjamin Rush is perhaps one of the first to make mention of this idea, when he writes about the different stages he notes for settling new land. I review this and his essay in its entirety at my page “1786 – Benjamin Rush – An early rendering of Sequent Occupancy” https://brianaltonenmph.com/gis/historical-medical-geography/1786-benjamin-rush-an-early-rendering-of-the-sequent-occupancy-philosophy/

Coverage of these different stages in development using the term “Sequent Occupancy” was initiated in the late 1800s, by

Derwent Stainthorpe Whittlesey (1890-1956). This philosophy was again focused mostly on economics and no evaluation of it in relation to place and disease was made. At the time, the notion of stages of development and disease were under review by a writer who would later form the popular epidemiological transition theory or model.

Abdel R. Omran and two Navajo

Original photograph is in the Archives & Special Collections, Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library, Columbia University Medical Center, New York, New York. The archival caption for this photo reads: “At Window Rock, the headquarters of the Navaho Reservation with Mrs Annie Waunika, the Chairman of Health Committee of the Tribal Council and Mr. Selth Bejay, the late delegate to the Tribal Council for the Many Farms area.” Source: Abdel R. Omran, “Use of the “Epidemiological Approach” in Evaluation of Tuberculosis Case-Finding by Tuberculin Testing of Young Children in an Area with Underdeveloped Resources.” Doctor of Public Health thesis, Columbia University, 1959. From the article by GEORGE WEISZ AND JESSE OLSZYNKO-GRYN , entitled “The Theory of Epidemiologic Transition: the Origins of a Citation Classic”, JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF MEDICINE AND ALLIED SCIENCES, Volume 65, Number 3 , p. 287-326, accessed on March 24, 2012 at http://www.mcgill.ca/files/ssom/OmranFiinal.pdf.

In the above photograph that is often posted about Omram’s work (often posted in reverse I might add), he is standing next to two Navajo people. This was right after the human genetics movement commenced; a generation before his work, the focus was on the “very healthy” Indian and the “Healthy gene” theory then being published. This notion was initiated by the observation that Navajo and other Plains Indians residing in reservations often had what later became know as “Athlete’s heart.” (See my page “Culturally Bound II . . . ” for more on this — https://brianaltonenmph.com/6-medical-anthropology/culturally-bound-syndromes-part-ii/ )

The third stage in Sequent Occupancy publications came in the 1960s into 1970s. The most important of these writers was Alfred Meyer. (Source for above figure: https://brianaltonenmph.com/6-history-of-medicine-and-pharmacy/hudson-valley-medical-history/1795-1815-biographies/john-w-watkins-natural-products-land-use-and-health/1778-to-1795-the-first-settlers/ ) This is depicted in more detail in the next two figures.

The first of these sequent occupancy figures is from a mid-1900s writing on this theory. Specific diseases occur during specific periods of development, due to occupation and lifestyle related disease etiology (causes).

In this next illustration of the same, related to the outbreak of an unidentified disease during the 1700s on the islands just off the shores of Rhode Island, (which I try to identify on that page– https://brianaltonenmph.com/gis/historical-disease-maps/yellow-fever/1763-the-extraordinary-disease-of-marthas-vineyard-and-nantucket/) , we get a closer look at just the Colonial and early settlement periods during a region’s different stages of economic development.

We can relate these methods of interpreting social changes to the Cree and other indigenous cultures that interacted with incoming explorers, trappers, business agents, and European settlers.

Alberni Indian residential school.

Male students in the assembly hall of the Alberni Indian Residential School, 1960s. United Church Archives, Toronto, from Mission to Partnership Collection. [Source: IndigenousFoundations.arts.ubc.ca]

This topic I cover in numerous places.

See my pages on:

Epidemiological transition

Community Health in Transition