kommabacillus Vibrio cholerae (wikipedia)

The following is a summary of the thesis I wrote for my MS in Geography, completed in August 2000 at Portland State University, Portland, Oregon.

The entire thesis is posted at another blog: http://oregontrailcholera.wordpress.com/. It is provided in sections, as multiple pdfs.

I have also included at this site three of the original chapters from this work. These first penned in the late 1990s, but pulled from the thesis submitted in Spring of 2000. They focus mostly on the history of medicine review I did prior to studying the two forms of cholera on the trail.

These chapters focused mostly on the history of medical geography and are a nice overview of how this field developed over the decades. Since they were not in the thesis, a few references aren’t fully cited. I post these because they provide important background information on medical geography/medical climatology. The related “Thesis References” section is worth reviewing as well.

I scanned most of these 19th C medical geography documents and will add them to the other site over the next several months. Mid-19th century medical journal articles related to the Oregon Trail were also scanned. These are few and far between and many deal with topics related to the Trail or the Far West, instead of medicine on the Trail.

.

I developed this work as a consequence of all of the misconceptions I saw in the writings on Oregon Trail medicine. During this time I was duplicating my previous efforts on Revolutionary War doctor Cornelius Osborn’s vade mecum by reviewing the vade mecum and ledger of Illinois-Oregon Trail-Oregon State physician John Kennedy Bristow at the Oregon Historical Society. During the course of my review of Bristow’s life, I came upon some of the statements that various authors made about “cholera.” This resulted in a fairly common mistake made throughout the literature in which the “cholera” epidemics of the periods of 1840-1848 were consider identical to the Asiatic cholera epidemics of 1832-1833 and 1849-1854. Due to the major differences between the other diarrheal disorders and Asiatic cholera, this was not the case. The problem was proving my hypothesis.

Until the late 19th century, as the cause for Asiatic Cholera became documented, the term “cholera” was applied in a fairly generic fashion. It was usually applied to a number of serious and not so serious diarrhea diseases. It has traditionally been used to refer to the chole-like or biliary nature of a severe form of diarrhea common to Europe, usually a form of dysentery that resulted from very poor sanitation practices in the more heavily populated urban centers. The most misleading part of these writings however were the outcomes claimed for those forms of cholera differentiated as Asiatic Cholera epidemics, which made their way into Europe some time during the late 17th century. This form of severe diarrhea had a completely different presentation. Instead of very loose dark-colored, bloody or otherwise discolored stools, it produced very white almost rice-like stools, due to how the organism vibrio formed aggregates in the bowels just before defecation. This helped physicians differentiate it from the rest of the dysentery by the late 17th century. The most famous physician to publish these differences was none other than the famous Thomas Sydenham.

In spite of this early differentiation of the cholera from Asia and India versus the cholera associated with what is now dysentery and severe bloody diarrhea, this knowledge did not advance much through the 18th and early 19th centuries. As time passed, physicians became more familiar with another form of dysentery caused by the entamoeba, referred to as Amoebic dysentery. By then we had two forms of diarrhea disease induced by a microorganism. The only problem was both usually require human to human contact to make their way into new victims, or recent exposure to human waste and items infected by this waste. If such were the case for the Oregon Trail, then why did the Asiatic cholera cease spreading along the trail, allowing the less fatal dysentery to prevail?

It ended up that due to changes in population density as one headed westward along the trail, it seemed very unlikely that entamoeba could have caused the “cholera” event that made its way into Oregon in Winter of 1852/3. This meant that the organism responsible for the severe cholera-like diarrhea of the trail from Wyoming to Oregon had to be a more common microorganism, one that was fairly common to the region and endemic rather than epidemic in nature. This left me with the task of evaluating all the possible causes for diarrhea along the trail west of Fort Kearney and along the eastern edge of Nebraska and Kansas prior to the import of vibrio cholerae, everything from saline mineral springs water working very much like the modern magnesium citrate products to common food-related epidemics that can occur due to poor food preservation, poor food preparation, and poor sanitation practices.

Once the first migrations westward along the early versions of the Oregon Trail began to occur, examples of poor sanitation practices became easy to find as the years passed. As the more severe forms of diarrhea began to afflict the troops and trailblazers, simple cases of diarrhea recurring at various sites along the trail became the more serious cases of dysentery, in which bleeding often accompanied the passage of fairly gross and discolored stools. These new forms of “contagion” tended to afflict the troops and people taking these westward journeys if they camped too close to bad water or too close to the dead carcasses that littered the trail. Once again, as this form of cholera defined in the more old-fashioned sense began to prevail, people misinterpreted these events as continuations or repeats of the Great Plains Platte River Asiatic cholera events. But this western version of dysentery was different from the “Plains Cholera” striking the midwest. This dysentery typically occurred adjacent to poor sanitation regions with carcasses set up in the just the right places to the local waters. It was carried to people by one of the most common vectors around–flies that landed on carcasses, food and people. There was also an “Opportunistic” nature of this dysentery that very much differentiated from Asiatic cholera. The “opportunity” this disease organism took advantage of was the reduced immune system people edveloped due to poor nutrition and long periods of overactivity–a result of the migration that had its greatest impacts upon pioneers as they made their way into the Far West.

This understanding of the various causes for diarrhea enabled me to define the two regions for “cholera” along the Oregon Trail. The earliest forms of dysentery would have prevailed in regions where numerous buffalo were slain and left to rot by the hunters. In regions where buffalo and cattle meat were left to decay, cholera of the dysentery (bloody or dark stools) form could prevail. Once the horses and oxen travelling along with pioneer families began to die, these regions where the carcasses lie also developed their own unique forms of cholera. Finally, due to ongoing conflicts between Great Plains Indians, sections of the overland trails passing through former settlements had buffalo parts strewn about, left to decay due to a recent skirmish amongst Indian groups. The bacteria rotting and contaminating the meats, went on to infect the waters. Immediately after passing through these settings, trailblazers would often note the cholera that set in due to the bad air they had to pass through where the rotting carcasses laid. The earliest note of this type, with frequent recurrence, uncovered during my research occurred at the eastern end of Nebraska along the bend in the Platte River where a Pawnee settlement once stood, but was reduced to trash by Sioux Indians just before the trail season began. Likewise in parts of Iowa, there were plenty of streams and other places for dead carcasses to lie and infect nearby drinking waters. This was a much less frequent occurance however, due to the fairly infrequent deaths of animals taking place so early in an otherwise very long migration.

This dysentery form of “cholera” was replaced by the Asiatic cholera following the re-introduction of vibrio cholera through Louisiana via overseas ships docking there. Following the introduction of Asiatic cholera to Louisiana, it would make its way inland to the jump-off towns in western Missouri like St. Joseph. It was from these Jump-off sites that Asiatic cholera made its way onto the trail each summer from 1849 to 1853, so long as it was introduced to Louisiana or some other eastern urban setting close to St. Joseph from which it could spread. Since this disease requires warm climates to prevail, it usuallyu would not make its way onto the trail until the late spring weather began to take hold. The Oregon Trail became warm enough to support this epidemic only once the last snow and ice had melted. This characteristic made the distribution of Asiatic cholera and vibrio into the North American continent quite easy to predict. It was a consequence of the biological and ecological behavior that the bacterium responsible for Asiatic cholera had, which was fairly predictable once you understood this temperature-disease association, even without knowing it had a microbiological cause.

Later on along the trail, in Oregon, with the Asiatic cholera now subsided due to lack of adequate numbers of trail people and settlers to infect, the dysentery returned, this time due to the Salmonella intermedia common to animals, infecting people that passed by these animals through the previously defined water and vector-related disease diffusion processes. These cases were rarely fatal, however. These infections could easily result in dysentery that lasted as long as 40 days, and sometimes more or more. Unlike the commonly fatal Asiatic cholera, this dysentery rarely fatal and more discomfort many of the pioneers had to endure for weaks on end. The biggest years for this carcass-induced scourge of the Plains were 1852 and 1853, as many of the trail diaries tell us.

Physicians interpreted these different forms of cholera primarily as a consequence of the local climate changes and meteorological conditions, and local topographic features. In regions where the soil was rich in saline and alkaline salts due to the local springs, heavy rains replenished the waters in which vibrio choleraa could survived for just a few days, long enough infect the next pioneer taking a drink from this impotable water source. This Asiatic cholera was very different from the earlier pre-1849 cholera to strike the same parts of trail during its most active years. For a variety of geographic reasons, the behavior of each of these forms of cholera could not only be better understood regarding the trail and its history, but also predictable and diagnosable based upon the symptoms and mortality of these two forms of “cholera”.

Ecology

When we look at the distribution of cholera in other countries, we find it is a disease related to an organism native to the India-Bangladesh shorelines. The comma bacterium Vibrio cholera evolved within the natural setting of a deltaic environment. Its existence depends not only upon interactions with the various organisms in this area, but the interactions these organisms have with other parts of the food chain such as bottom feeders, shellfish, and consumers of these foods sources, like man.

Vibrio resides naturally in the brackish seawater of the delta that empties into the ocean water, and tends to infiltrate the “gut” or innards of a particular invertebrate that naturally resides there. This internal environment changes the vibrio and makes it more active as a potential pathogen, but it is still not a disease agent during this early stage because it hasn’t yet infected any humans. The vibrio next makes its way into people via the food chain. As the microorganism is ingested by filtering shellfish like oysters, and taken up by fish along with sea water, it infects the innards of these organisms as well. Sooner or later, these organisms get harvested and become a part of man’s diet, such as in the form of a raw oyster meal or some form of seafood plate. If the vibrio survives the cooking process involving these foods, it can make its way into the human digestive tract. This leads to the development of an Asiatic cholera diarrhea episode, which can be severely dehydrating, debilitating, and deadly, and ultimately more infectious and now highly contagious.

The other way this vibrio makes its way into the human gut is by drinking water contaminated with the vibrio itself or by imbibing water infected by a microorganism carrying this vibrio. In some settings, this is all that is needed for epidemics to erupt. In nature, one of the best places for this to happen is where water that is salty like seawater, meets up with water that is brackish, carrying in it large amounts of nutrients. This feature is typical of delta environment waters where the fresh and brackish water meets up with oceanic water, and large amounts of biological waste settle along the bottom and edges of the delta’s unique sediment formations.

In North America, the Mississippi delta meets these environmental requirements for vibrio and is more than likely a place where vibrio has tended to reside for much of the United States history. Once it was introduced to this region for the very first time in the early 1800s, the vibrio probably never left this ecosystem. We never see it erupt into large-scale cholera epidemics because the requirements for such an epidemic were not present for most of the time. Yet throughout the history of this Louisiana-Texas-Mexico Delta-Gulf setting, there have been ongoing incidents in which Asiatic cholera cases have erupted in single individual and families, without an ascribable biologic cause. This suggests this choleric organism is a natural part of the local ecosystem, but not a part of the normal human ecology for most of the time.

What enabled this organism to come to the Oregon Trail and make its brief stays there were weather, people and prbably the saline-alkaline waters produced naturally along Platte River that improved upon the ability of vibrio to survive between people, like in water wells and latrines. Both the environment and the ecology needed for vibrio to survive existed along certain parts of the Oregon Trail.

Climate

Aside from the natural ecosystem requirements, certain meteorological requirements exist as well in order for vibrio to interact with humans. One way to think of this relationship between temperature and disease is to envision the human intestinal tract as some sort of equivalent to the deltaic environment where vibrio thrives ecologically. There has to be detritus or some source for nutrients (in people this is the food being digested),the right temperature, and the right amounts of ions and such creating a brackish water like saline environment with the right pH. By interacting with the intestinal lining, the vibrio can make the body release salt into the gut and make the intestinal environment more supporting of the biological and reproductive needs of the vibrio it carries. This salt into the gut, primarily sodium, results in vibrio population growth at a very fast rate, in turn leading to further salt and water loss into the gut, causing very watery stools with a white rice-like appearance. The white lumps are vibrio aggregates.

Climate sets the stage for this to happen in that the right temperature requirements have to be met in the organism’s natural setting–such as the water of a delta system, or more inland, a mineral spring with a fair amount of sun exposure and detritus in it. Thus climate and temperature make it possible for the vibrio to become reproductive, able to move about its ecological setting by infecting carriers of the bacterium, and ultimately make its way into the next person’s intestinal tract. In this way, the Asiatic cholera case diffusion process can be traced based upon temperature features, with potential hot spots for its natural evolution defined based upon soil pH and mineral/salt content, and potential epidemic regions defined based on local human population features. The ability for a newly erupted case to re-erupt is based upon features that enable the vibrio to survive between human victims, and come upon new potential candidates for the disease in a short enough time, while the vibrio sits in a natural medium supporting its growth and continuation of life.

Spatially defining Disease Patterns on the Oregon Trail

There is a unique relationship that exists for the Asiatic cholera and its organism vibrio. There is a natural setting in which vibrio thrives without need for human involvement, and another environment in which vibrio becomes capable of thriving and perpetuating its species in rapid succession as one generation after another of vibrio are produced and ultimately leads to one or more new genetic types being produced that become more efficient as disease-causing pathogens in humans. Two Russian geographers managed to effectively describe this natural process the disease causing pathogens were taking. Voronov and Pavlovsky detailed this ecological event as having several parts or pieces of the puzzle.

Since Asiatic Cholera epidemics are dependent upon large populations to persist in a given region, and a certain kind of climate or weather and local ecological setting to prevail, this meant that it was unlikely to have been a regular part of Overland or Oregon Trail. This meant that the pre-1849 cholera epidemics (as early as 1844/5) seen in eastern and western Nebraska were not Asiatic cholera. (As previously stated, they are generally accepted to be a consequence of a Sioux-Pawnee Indian dispute and the rotting of buffalo hides left behind.) This also meant that it was impossible for Oregon to suffer from Asiatic cholera when it did due to the time of the year that it struck and the poor population density in the area (1853, spread in the winter via Astoria into Portland).

The thesis defines two disease regions for two different forms of “cholera”. The first region closer to the jump off sites consisted of rue Asiatic Cholera events. The second was formed by an “unknown cause” (later identified as Salmonella intermedia) for severe diarrhea or dysentery. I then defined a zone where either type of diarrhea could have prevailed, the epidemiological transition zone. By reviewing the trail diaries in detail, I was able to develop and support, and later confirm this suspicion.

Once I confirmed the fact that Asiatic Cholera did not make it way to Oregon via the trail like many scholars were speculating, and that this form of cholera also did not exist along the Great Plains along Platte River like even more scholars suggested, I still had to identify the cause for the second form of severe diarrhea. This required some fairly humorous reviews of the diaries and reminiscences, with the goal of obtained exquisite details on the kind of diarrhea people experienced along the trail. I needed a description of the diarrhea and details about how many times it struck and where. To rule out Asiatic cholera, this diarrhea had to be something other than “rice water” stool in appearance, and rather a stool of any other color, and primarily bloody. In addition, these bloody diarrhea periods had to last more than just a few days–in fact, lasting as long as 20 or 40 days. These latter two symptoms were typical of “dysentery.”

The final question to answer is why did these spells of diarrhea happen? It ended up that I was able to link the spells of diarrhea to topographic features along the trail–the rapid ascent of steep trails at high elevations by fatigued animals was responsible for the build-up of smelly, decaying carcasses (to put it bluntly). This rules out the forms of bloody diarrhea or dysentery that are like Asiatic cholera–in need of people to continue their spread across the Great Plains. The remaining question then became, what typical bacterium associated with dead carcasses could be producing dysentery-like conditions in people. This required that I rule out other common causes for diarrhea such as drinking too much mineral water, or becoming a victim of Giardia (Giardia has a different primary symptomatology than just ‘bloody diarrhea’, in particular involving flatus), once again eliminating the possibility of entamoeba (Amoebic dysentery), and ruling out such bacteria as yersinia (the plague) and even Escherichia coli. This meant I had to match the symptoms noted in the diaries and journals with these other possible cause for “bloody diarrhea”.

During this course of investigative epidemiological research I was also able to differentiate another disease often associated with the trail cholera from the dysentery cases–Mountain Fever, now known as Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever. Mountain Fever had its own ecological requirements for onset. Since it was due to tick-ridden areas bearing specific forms of plant and animal ecology, it occurred in the mountainous settings mostly in western Wyoming, and from there into Idaho. Again, the geography of the trail meant everything to understanding what kinds of diseases the overlanders were experiencing during their travels.

The final spatially-defined disease association that came up during the course of this research was the possible onset of a milk sickness epidemic along the trail, the victims of which were mostly young children and newborns being fed oxen or cattle milk. The distribution of this disease was dependent upon the distribution of its most important cause along the trail–a plant which the cattle ate, a species of Eupatorium, now well-known for causing these well-localized epidemics during the 1820s period of Bible Belt history.

When it came to presenting this work upon completion, I came to refer to this project as a complete study of “Diarrhea along the Oregon Trail”, an amusing name for a not so happy piece of Oregon Trail history. This work took several years, and a lot of work in several fields of science and history before it could be completed and submitted as a thesis. It required a study of past trail diaries and reminiscences, fort documents, disease-weather studies published during the 1800s, much of the cholera literature for the time (all 500 or so 19th century articles which my library provided me with), and numerous side studies on each of the possible alternative causes for diarrhea along the trail, ranging from salmonella to shigella, to entamoeba, to giardia, to the infamous enterotoxic E. coli O157. In the end, knowing the outcomes and causes for each of these diseases was well worth the three years it took to complete this study.

OTHER STATISTICS, GRAPHS, TABLES, CHARTS FROM THESIS (Body and Appendix)

.

.

A very similar figure appears in a 2000 edition of Medical Geography. The two were developed separately from each other, I think.

.

.

.

.

.

.

The more children you had, the less likely you were to risk travel.

.

Notice the two large peaks coming through Umatilla Pass. When people departed, they departed as groups or clusters, which together formed chains once they were on the trail. This crowding increased susceptibility for disease spread and accidents, and later exposure to unsanitary living environments. We read a lot about families being isolated or in clusters of a few family and neighbor wagon groups, but there was also this tendency to travel together for purposes of survival, protection, and passing the time in the evenings. Culturally similar groups would have bound together more than ethnically or culturally dissimilar groups. Since disease prevention and behaviors are very much a product of cultural beliefs, this made it possible for a entire family or the bulk of some families to be wiped out. The Irish tended to be self-consoling with illness, the Germans according to my Cincinnati, Ohio and Warren County, Illinois studies (and related published articles) demonstrated a tendency to close the doors and windows whenever an epidemic erupted (fear of miasma spreading between wagons).

.

.

For the most part, twenty to thirty years were the argonauts.

.

On the Trail, the young were very susceptible. Notice the peak in the 2-10 yo deaths along the trail (above figure), versus those trails deaths noted for people removing to California (below figure). This may be simply due to reporting, but could also be due to people’s behaviors with regard to reporting their children or their deaths, or the tendency for younger adults to engage in the migration for the pursuit of gold. The Oregon Trail research demonstrate that older adults and middle-aged adults were susceptible to Asiatic cholera just after Fort Kearney, due most likely to contamination that took place at and in the Fort itself or by use of its water. An aqueduct that travelled in a northeasterly direction connected the Fort to the River, adding more options for how the disease could be diffused. Diaries detail the many deaths that occurred in clusters within 1-3 days of leaving the Fort. Diaries also reveal a second series of deaths out west in Nebraska, just a few days before Fort Laramie. The common though is these deaths, many being children, were due to children simply becoming ill, often which cholera infantum. There were two plants (a Eupatorium sp. esp.) out there that poisoned the milk of cattle eating them, and subsequently any cattle milk fed babies.

.

.

The above table depicts clusters or aggregates of people residing in close quarters. These served as niduses or nests for infectious disease transmission. Crowded quarters combined with poor sanitation practices involving cooking or latrine management would have increased the susceptibility of people becoming infected. The obvious diseases like measles, pox, and the like could have developed in these settings, especially for the quarters where orphaned children resided, but most likely they served as niduses for dysentery and the like. Those inhabited by sailors and other ship staff would have served as avenues of entry for this region for foreign born diseases. The Soldiers of the Columbia Barracks were the most likely, most susceptible candidates for disease in-migration for the most part. Madame Superior’s Clatsop orphanage (which brought in orphans from afar no less) was also a very likely place for people-to-people epidemics to enter the region, like measles, mumps, pertussis, and dysentery.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

..

ADDITIONAL FIGURES, GRAPHS, IMAGES, ETC.

.

This next section consists of summary graphs, tables, images, illustrations, pulled from my research notes for this project.

During its early stage a lot of time was spent reviewing demographics and transportation in the US, west coast and Pacific Northwest. This included a review of three newspapers: one each published in San Francisco, Panama (Panama City?), and Sandwich Islands. It was typical for newspapers to record the ship names, country of origin, holdings, number of passengers, place last departed from, and next destination, all in list form near the end of each issue. [Once I find the excel file this will be put on this page.]

Other data came as tidbits of graphs, tables, etc., from the medical journals–all of these are listed in the bibliography attached to an early rendering of the work. Many of these were evaluated and so the graphs, etc. appear here.

Since there were done in the very early stages of this work, some are labeled badly.

I divide this work into the following categories:

- Weather

- Topography

- Demography

- Transportation

- Epidemiology

- Summary Items or Figures

Each category pretty much presents information in the following order of regions: National/US, West, Midwest, West (mostly California), and NW (Oregon)

.

.

Weather

The above and below are developed Alexander Keith Johnston’s description of the tropical, temperate and arctic zones of the earth. This is how his writing might have been interpreted without seeing the actual map.

.

California meteorology-focused medical geographers began their recording of daily temperatures as early as 1848/9. The following was from a published report on this activity.

.

People into climate and health looked at the major fluctuations in annual temperatures. It would decades later be considered for high temperature differences between winter and summer to be stimulating of health for those with consumption (see my work on Denison). Elevation also played a role in determining the healthiness of a setting.

.

.

.

Fort Vancouver was most stable in terms of temperatures and therefore health. Fort Stephens offered the major max-min differences often recommended for treating consumption. DC is District of Columbia.

.

.

.

(Reporting/recording error)

..

Topography

.

.

.

.

.

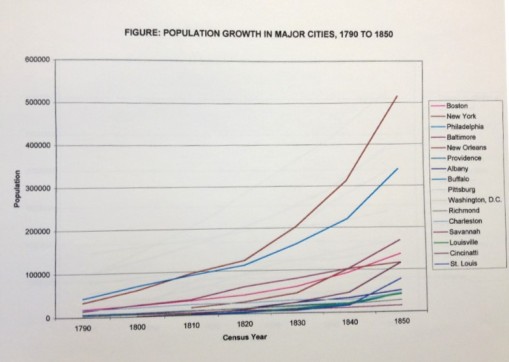

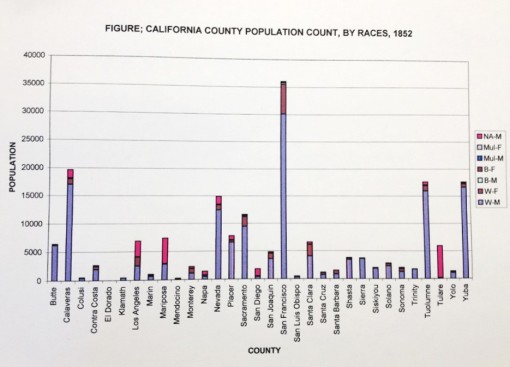

Demography

.

Black, White, African American and Mulatto are detailed.

.

In migration of people, by year, during the earliest pioneering period.

.

.

.

.

.

.

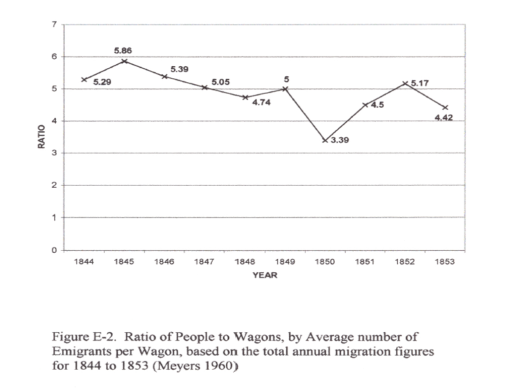

Transportation

.

.

.

.

.

Epidemiology

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Summary

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

.

Summary