OVERVIEW OF MY CHEMOTAXONOMY-ETHNOBOTANY RESEARCH DURING THE ACADEMIC TEACHING YEARS

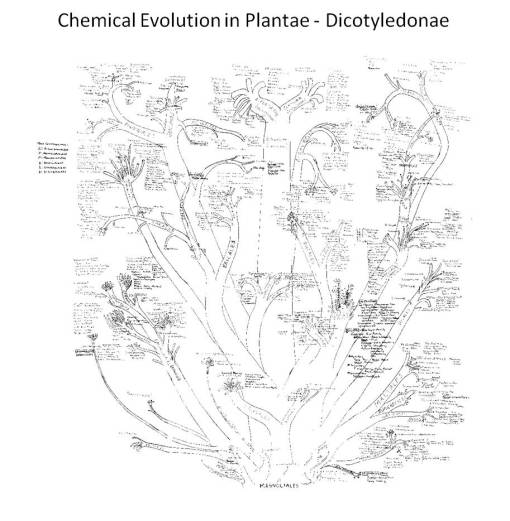

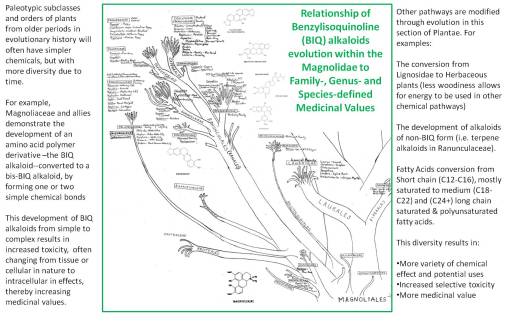

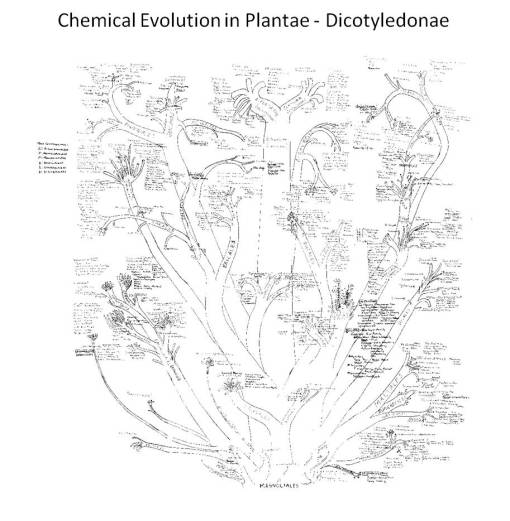

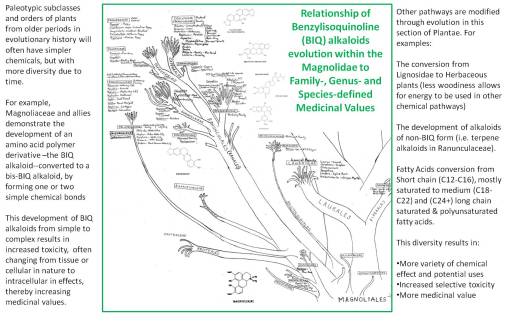

PLANTAE MEDICA was the title for the book I wrote to teach my course on the Evolution of Natural Products. This book was written for classes that began in 1989 and that I continued to teach until 1993. During this time I upgraded the book, improved upon my phytochemical evolution charts, and added some figures and tables as a result of my tabulation of the ethnopharmacology and ethnobotany data, the uses of 10,000+ plants drawn from the ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology dictionaries. This main attraction for my course was a handout and later a purchasable item I developed due to my work in the labs–a chart I began to produce in the winter of 1987/8, the first 6 months of my research on the evolution and change of the Magnoliidae, Dilleniidae and Rosidae in relation to their benzylisoquinoline alkaloids (BIQs), lignans, and coumarins. This work was then extended to include the remaining dicot subclasses, and a year later all other plant Classes.

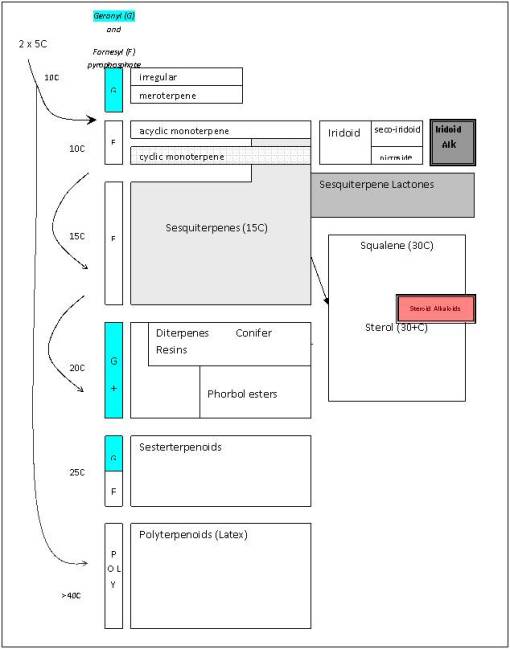

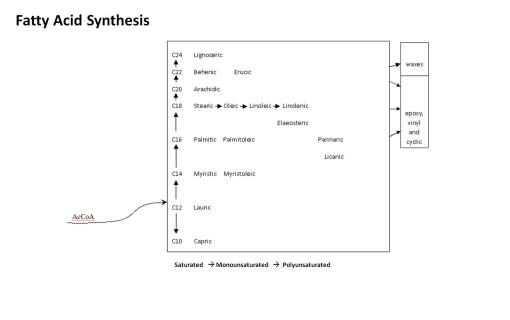

These charts were then used to determine if there were any more plants in the Pacific Northwest Old Growth forests, aside from three I had already uncovered, that bore cancer drugs. At the time I was researching the reasons for the evolution of homechelidonine, sanguinarine (two BIQs), thalicarpine, thalictrine (terpene alkaloids in the same Subclass), epipodophyllotoxin (a lignan), and the coumarins (the route these plants take in their synthesis when they don’t produce cancer drugs). Over the next two years, my evaluation of plant drugs and potential chemotherapy applications covered the entire gamut of secondary natural products pathways. As I added these pathways to my notes on the taxonomy chart, certain behaviors of plants became apparent regarding how and why they synthesis these chemicals. A review of the evolution of fixed oils, terpenoids, and phenolics in relation to the paleohistory of plants confirmed this theory for me.

The evolution of natural products thus became the major theme of my course on chemotaxonomy and natural products evolution for the next decade. Plantae Medica essentially presents the plants in a taxonomic order, with sections detailing some of the unique chemical pathways evolved and natural products that resulted from these changes brought about through phytochemical happenstance and evolution. Because this kind of interpretation of plant chemicals is so different, and fairly concise or to the point, I tended to sell twice as many course books as I had students over the years. For this reason I am working to rewrite its contents along with the material contained in my 20 years of teaching notes in this field. These are planned for a separate set of folders on this blog site.

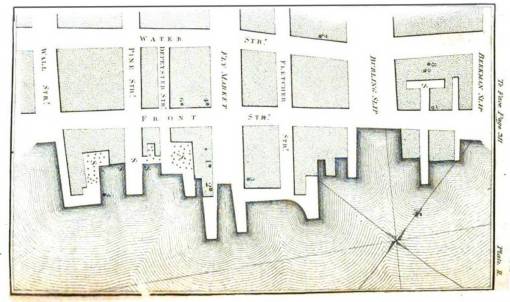

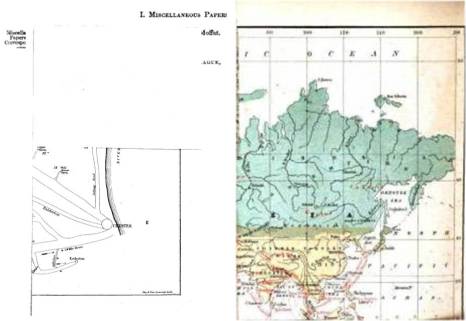

1988 lab notes on chemical evolution in dicots, based on Bessey, Dahlgren, Thorne and Hartshorne. Plant chemicals follow specific synthesis pathways, depicted in the above taxonomic tree.

.

The History of This Research.

As many of my friends know, I began my explorations of plant chemicals due to my interest in plant poisons. As a high school student, I taught various nature and conservation programs and gave edible wild plants and survival classes for the local Boy Scouts summer camp in middle New York. During this time, I accidentally ate a Swamp Iris rhizome in the early spring (April or early May of 1971 I believe, before the leaves were even a foot tall), thinking it was a cattail rhizome. An hour later I accidentally bit into the undercooked tuber of a Jack-in-the-Pulpit (Arisaema triphyllum) root, thus experiencing for the first time a strong burning pins-and-needles feeling in my mouth induced by the oxalate crystals that never dissolved during the boiling (the corm essentially was undercooked).

The next book I bought was Douglas Kingshorn’s Poisonous Plants, followed by several more on poisonous plants related topics including the then classic Mushroom Handbook published by Dover. (I often foraged for mushrooms as well.)

Two and a half years into my naturalist work with the local Boy Scouts, I spent some time working for the Clearwater Sloop organization, and then joined an ambulance corps and became an EMT about a year later. My interest then had turned mostly to toxic chemicals (pollution, industrial and household chemicals), drug abuse (heroin was the big one for the time), and poisons. After several months of ER work dealing with drug ODs, almost on a daily basis (with heroin and alcohol the main reasons), I was encouraged by the ambulance corps staff to consider going to college. A Vassar College student I had partnered up with for the EMT course was pre-med, and so recommended I consider the state university on Long Island for its sciences/pre-med program.

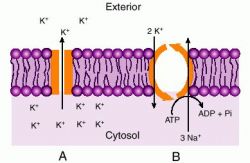

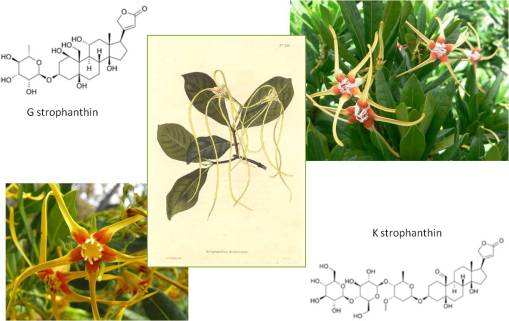

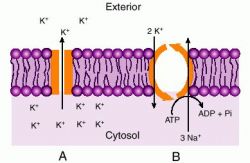

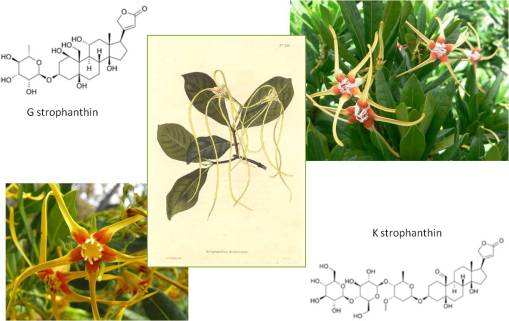

Upon entering the pre-med undergraduate program in biology at Stony Brook, I quickly got to know my roommate, a sophomore who specialized in neurophysiology. After discovering that my interests and knowledge were pretty much fixed on toxicology, he recommended I interview with professor he did research for, for a research assistantship position similar to his own. A week later, I was hired as a research assistant with a professor in the department who specialized in squid axon Sodium-Potassium channel physiology and biochemistry. Since I was also enrolled that same year in a course taught by Professor emeritus Adrien Albert of Australia, who specialized in selective toxicity, I immediately related his teachings to my interests in neurotoxicology and plant poisons and my research lab activities, and so the story goes . . . . The professor whose lab I did most of my squid axon research in shared this lab with Professor Jakob Schmidt, a specialist in receptor physiology as it pertains to Cone Snail Venom (famous for its highly selective, neuro-, cardio- and myotoxins). By the end of my second year in college, most of my research turned to research on the selectively toxic activities of tetrodotoxin, bufotoxin, triethanolamine, ouabain, strophanthin G, aconitine, various digitaloids, pilocarpine, physostigmine, purified enzymes extracted from snake venoms, etc., etc.. All of this just to better understand the physiology and mechanics of receptor binding on the neuron, by way of interpreting changes in membrane potential and the relationship of these findings to the Michaelis-Menten Na+-K+ channel model.

By the third year, had complete all of the undergrad neurophysiology work and was heavily into marine toxins (fish, shellfish, coelenterates, and nudibranchs), and so began frequenting the beaches and channels along the northern shores of Long Island. By now, my work as an EMT had evolved into a training officership position with the campus ambulance corps, and my specialty of course was poisoning and drug overdose emergencies. This obsession with plant and animal toxins led me to purchase Anthony Tu’s Venoms and the fairly hefty reference Poisoning.

This probably would have been the way my research and biology work went, had I not been given the opportunity to work as a naturalist and natural historian for the Museum of Long Island Natural Sciences located in the Earth and Space Sciences building at Stony Brook. This was originally done so I could qualify for a second undergraduate degree in Earth and Space Sciences (being the typical, competitive pre-med student that I was, of course), but quickly turned from an independent study program to a half to full-time botanist/naturalist position.

My work with this department began as the cataloguer of plants gathered in the past by the local naturalists, for the past 10 years. During this time I learned a great deal more about plant taxonomy, a local pine barrens ecology project and several environmental protection programs underway. These programs included a program vying for public recognition of the local endangered plant species Butterfly weed or Asclepias tuberosa, a plant covered in all basic biology classes which tells you about the monarch butterfly, which consumers the plant’s nectar, which contains cardioactive glycosides, that in turn cause any birds that eat the butterfly to subsequently vomit, and so save the species. This plant protection program rapidly became popularized by the news (there is even something in Newsday about me and a lady being told that she couldn’t run her lawnmower over the foliage, in order to protect the Butterfly weed growing in her yard).

I maintained my museum position as “herbarium director” from summer of 1979 on, during which time I developed some of my own collections pertaining to specific local plants of local ethnobotanical history importance, mushrooms (of course, I was into most of these due to their toxicity and the associated medicinal values), and produced numerous teaching specimens for the museum courses. In just a couple of months, this led the museum to make an offer to pay me for teaching outdoor classes on these topics, ranging from simple field trips through the local forests to actual accredited classes on teaching botany in the middle and high school science labs. Unexpectedly, these classes really took off, especially in herbal medicine, and subsequently landed me (and my students) a lot of time and airplay in the local and regional newspapers and interviewers. This, in turn, resulted in still more opportunities for me to teach these classes to local special interest programs and groups, and even spend some time with the local TV station.

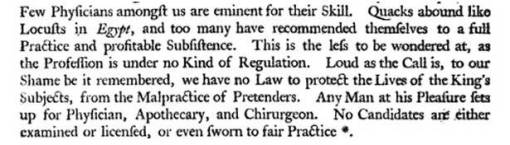

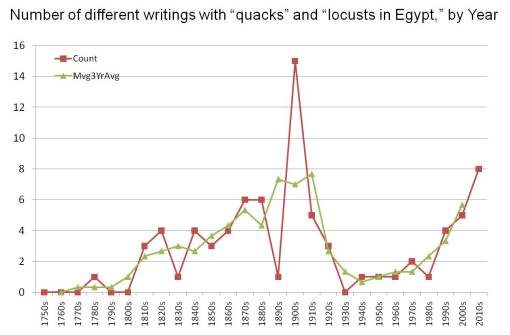

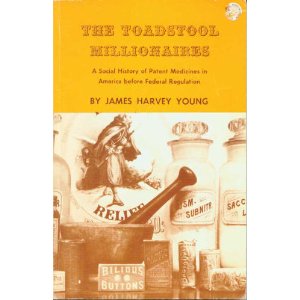

In Fall of 1982, I began taking classes in medicine at the local medical school, interested primarily in plant toxicology and the potential use of selectively toxic plant chemicals as medicines. The politics of plants and medicine at that time was really problematic, and yet funny. The grandfather of medical history at the time was a professor from upstate NY who popularized the notion of quackery as it related to herbal medicine use. This prevented me from saying much about my opinions on their value as medicinal agents. Throughout my first two years there, still teaching on main campus, I would find that every now I’d be in the news and a few days later receive some anonymous letter in my medical school on-campus mail box criticising me for what I am promoting, and teaching on main campus. Even one or two very close friends kind of ridiculed the idea of researching medicinal plants, especially during my time as a medical student.

So how did I, as a medical student, get to research this topic back in the 1980s?

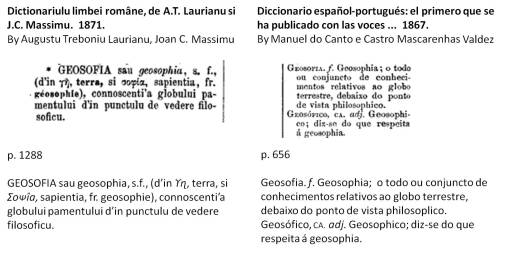

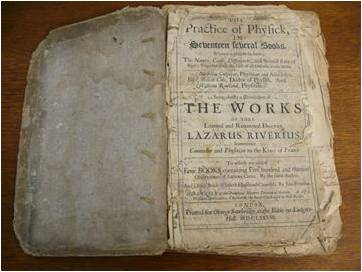

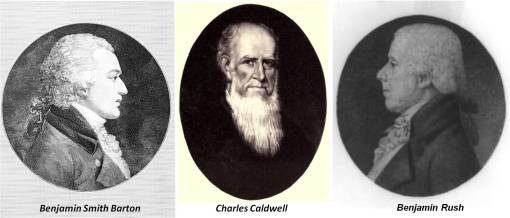

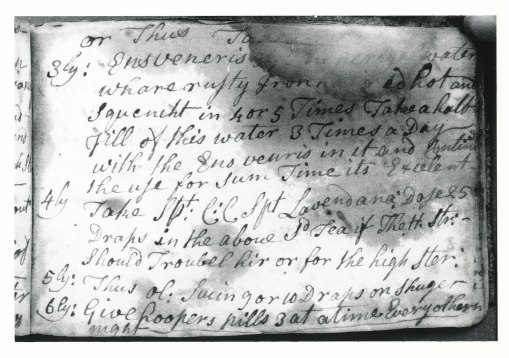

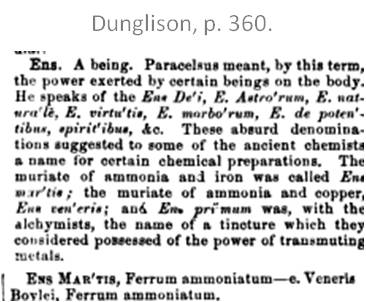

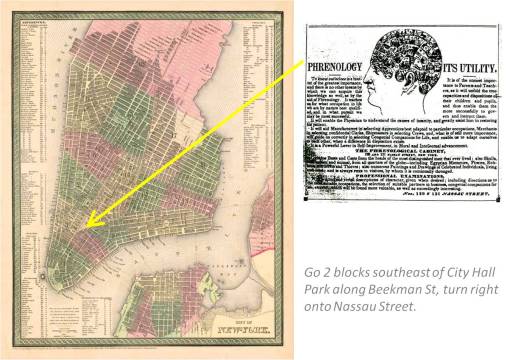

I managed to get some support doing this work by calling it a ‘history of medicine’ research project. Every summer, just before the academic year began, I wrote up a description of my research plan, as request by my mentor in the history of medicine. He would sign this proposal, allowing me to engage in regularly funded research on this project at the expense of the medical school’s internal grants and student financial assistance programs. During this time (lasting about 3 years), I specialized in Eclectic Medicine, since this field of study had the most scientific writings for the time (1825 to 1875) on plant medicines. I also researched a number of domestic recipes books, as well as the typical fields of alternative medicine (which the medical school of course had me refer to as “quackery”) including Thomsonianism (1812-1855, 1880s), Indian Root Doctoring (1780s to 1840s, for the most part) and Homeopathy (1823 on, 1837 on for NYC). It was also during this time that I began to decipher and translate a vade mecum (recipe book) penned by a colonial doctor in upstate New York, making use of the local plants.

During the next several years, I attended annual meetings of medical historians in New York’s Medical history library (once part of one of NY’s earliest medical schools). There, we members of the historical society would argue about the most important topics for the time. These historians were from the various mid-Atlantic and New England medical schools, and most were classical sociological medical historians for the most part. Their mentor pretty much kept popular his viewpoints on Quackery, left for him by an earlier AMA member and representative in charge of eliminating quackery from this field of practice, Morris Fishbein. Few had an interest on whether or not the herbal medicines of the past worked.

Also during these years, I made attempts every semester to enroll in a PhD program devoted to researching plant toxins for potential drug uses. The pharmacological sciences program affiliated with the medical school would regularly interview its candidates for this position, and I would apply every year. Each year, I’d go to the department’s for prospective students, hoping to find the mentor, grant money and professional support needed to engage in work much like what I had already done in the undergraduate neurotoxicology labs (one of these professors was even in the same department and building I worked in).

At the time, the politics of plant medicine made it difficult for me to obtain full department support for this type of work. And since the university had just been rewarded a multi-million dollar grant designed to bring to market the first immune system medicines to the industry–interferon–I was constantly reminded of this with each year’s discussion of my research interests with the pharmacology department staff, and by the pretty personal notes left in my mailbox each time I was in a local newspaper for my courses on plant medicine and edible wild plants.

The one topic I did obtain substantial support for at this time, but did not get into a PhD program for, was the development of a database (on a Wordstar/Datastar, Sanyo 550) useful for diagnosing plant and mushroom toxicology. A database with this information was already in place, on microcards and microfiche, but not in any computer-related database-query form. So, this first attempt to produce a computer-generated diagnostics tool useful for identifying plant poisoning cases based on symptomatology was initiated, with the limited support of two local experts in toxicology emergencies. To produce this database, I had to purchase the most up to date PC with CPM/SYS as its basic programming language form, a 2kb + 2kb hardrive, and the software needed to develop this database/diagnostics program-Datastar. I used the term “toxidrome” to define this program (it was called Toxidrom, 8 characters), because it was used to describe dozens of toxic syndromes associated with domestic and wild plant ingestion. As an aside to this small-local-grant-supported work, I also used the same software to develop an herbal medicine database, of course focusing on “quackery” and herbal medicine toxicity of these products, but also their history and use.

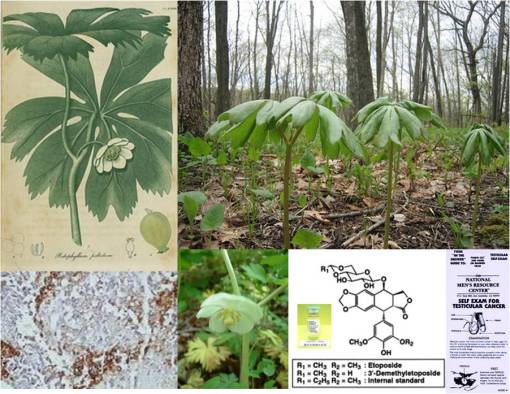

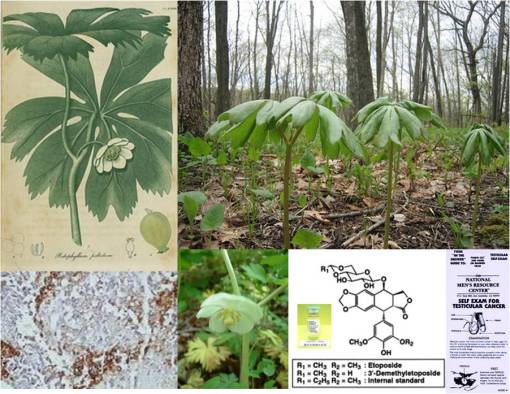

Interestingly, throughout this time researching the history of plant use in medicine, I knew my topic of interest was not dead. Each year, whenever it was time to apply for the MD-PhD, the pharmacology department head would meet with me, very cordially, because he was interested in updating himself on what I knew about plant drug compounds. We had discussed a number of projects that needed to be done in his lab, for example using the cardiotoxin strophanthin G and its derivatives to study membrane channel receptors, and we rediscussed the potential for researching several new neurotoxins, and more specifically the possibility of researching the rapidly growing cancer drug industry that existed for epipodophyllotoxin (today known as etoposide)–at the time I was researching other plants that I knew produced this drug locally (in particular, Podophyllum peltatum, the same plant used to make the Carter’s Little Liver Pills above), and had a few other plants with pharmacological industry potential which were of potential use as intercalating compounds for the treatment of the most active forms of cancer (esp. testicular cancer).

In 1983 and 1984, a number of people saw some shows that were aired about me on the local TV channels–apparently these shows were being aired in the hotels and motels in New York City. This led me to make contact with a pharmaceutical company, that paid me a lot for my time, to serve as a consultant in the field for a year (each Wednesday they would pick me up in a limo outside the front of the University Hospital). It also led a PR person from the only fully accredited west coast school at the time on alternative medicine to offer me a teaching and research position once I graduated.

The following year, during a trip out west (a follow-up on an offer due to another offer related to a TV clip shown on TV), I saw another cancer drug source being burned as a consequence of the slash-and-burn clearing methods employed to this region for its lumber-producing trees. The local Yew Tree, a source for the cancer drug taxol, was the fuel for most of the bonfires that I witnessed. I next contacted some associates on the east coast and talked with a number of people in the university, television and local news agency settings about this.

Three cancer drug producers in Oregon’s Old Growth Forests

This led me to compose a research proposal and presentation on the natural resources of that region applicable to the pharmaceutical industry. In January 1987, I was fortunate enough to be asked to discuss this issue on a local TV news show, as an expert in plant products along with many other natural resource experts; I mentioned the potential cancer drug-producer locally of taxol and the rapidly growing LEAR Oil industry about to take hold (low erucic-acid rapeseed oil, later known as Canola Oil, a bioengineered plant products food industry). Also present were a number of local graduate school professors interested in bioengineering at the time, only they had an interest in just making pulp for paper and saw no value in trying to bioengineer medicinal products, an accomplishment still years away from accomplishments they reckoned.

I could tell from these meetings that both the local scientists in bioengineering and the local forestry service workers were very poorly trained in the complete use of natural resources as sources for secondary products. Still, my exposure through this program was good for me. Soonafter, I was asked to give a similar talk to the Geography department at a local university, and so in February 1987, I discussed the potential applications of the new natural products industries to the diminishing local forestry industry. This work included my review of the importance of plant- and mushroom-derived products obtainable locally, as adjuncts to the local cottage and forestry-related industries, and the possible development of programs designed to make the best use of the local flora for phytochemical products. At this talk, I also defined the three cancer drugs native to Pacific Northwest forests: Libocedrus-epipodophyllotoxin, Thalictrum-thalictrine and derivatives , and Taxus-taxol and derivatives. (One of the foresters there, who followed up on this suggestion, later thanked me for this information and its ultimate success in the local cottage industries program just started.)

By the end of this talk on Pacific Northwest natural products, I was offered a lab to research plant chemicals in by the chemistry department, and was told that I could pretty much perform my own research, at my own speed and pace, in my own areas of interest, at the department’s cost for chemical supplies. Within a month, I set up a lab and was soonafter asked to write up a proposal on a course entitled “Chemical in Plants”.

.

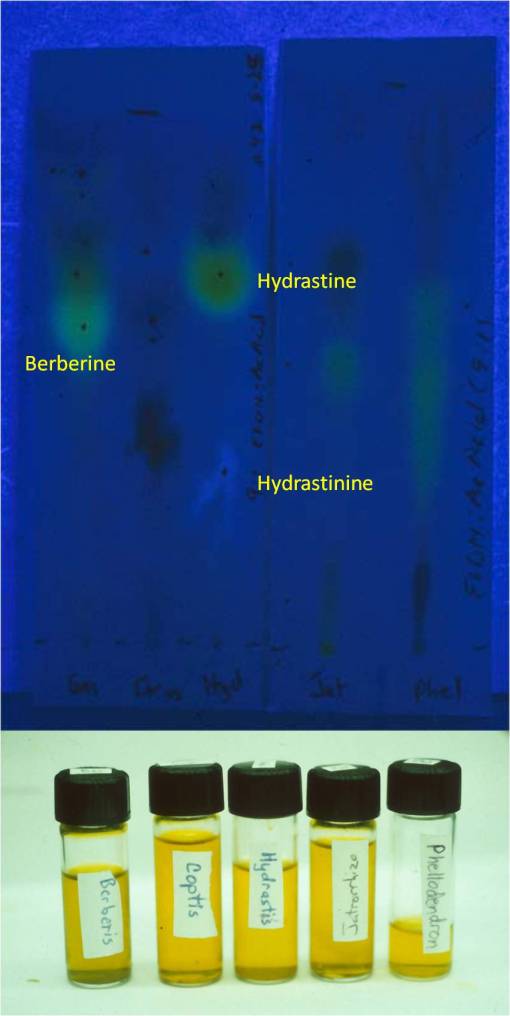

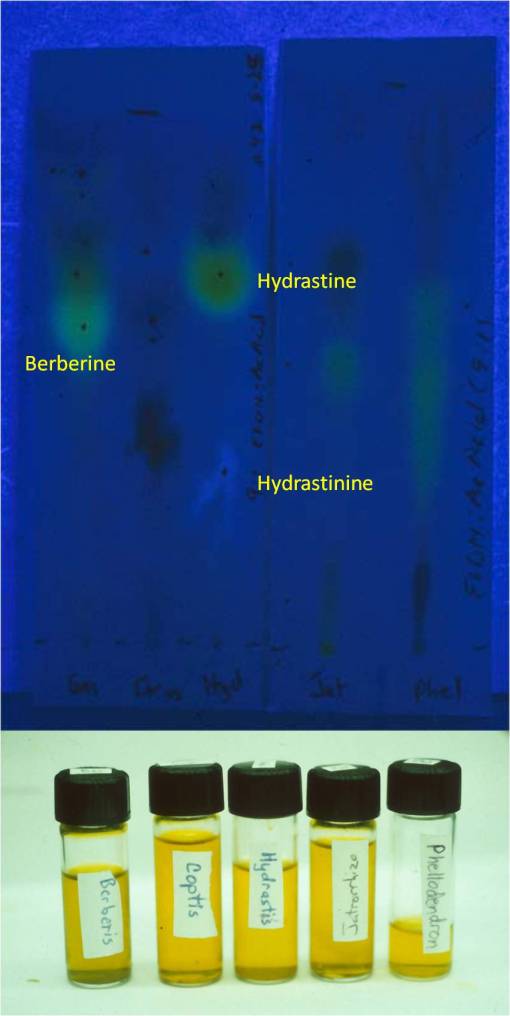

Thin Layer Chromatography results for one of my studies, 1987-9. Note hydrastine to hydrastinine conversion in Goldenseal, due to short shelf life as a powder (approximate shelf life, 3 mos., including packaging and storage). This converts Hydrastis from an antibiotic, a common claim for the hydrastine in it, to a smooth muscle relaxant due to the hydrastinine.

For the next 17 years I taught this course and its various modifications devoted to plant tissue culturing, bioengineering, chemotaxonomy, tropical and northwestern rain forest products, Oregon history natural products, etc., and I used this lab to study my various groups of plant chemicals, in particular those that were selective toxins. I was particularly interested in alkaloids, but not the commonly known neuro- and myo(myelo)toxic varieties any more, but rather the benzylisoquinoline alkaloids–which contained several types of cancer drugs in need of further investigation and testing for clinical use in treating the toughest forms of cancer cases. I also took this opportunity to once again spend time investigating podophyllin-like neolignans in plants such as the local Mayapple (Podophyllum) relatives Vancouveria hexandra and Vanilla Leaf (Achlys triphylla). I worked out the mechanism by which Achlys was producing coumarin mostly after it was detached from its rhizome. I documented the overharvesting of the local ginseng-substitute Oplopanax (Devil’s Club) by local cottage industries devoted to herbalism (this was during the spotted owl years and news episodes.) When I was asked to present at an annual meeting held by local wildcrafters, I developed a list of about 50 underappreciated local natural products that were out there, as defined by their chemical and non-chemical uses. I presented these results at an annual meeting of harvesting companies held at the state Capitol building in winter of 1990/1. A new program was then developed requiring harvesters to register for and obtain harvesting permits for old growth forest plants in order to prevent overharvesting.

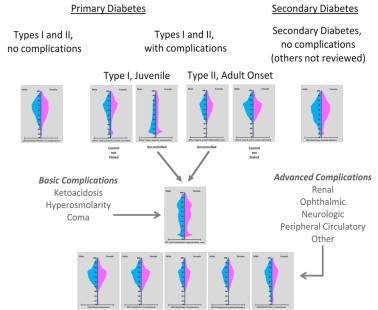

Common Benzylisoquinoline alkaloids and allies in herbal medicine

Over the the next decade, I researched sesquiterpene lactone toxicity and the curious case of lumberman’s lung disease brought about my it, essential oil-, iridoid- and flavonoid-chemistry and taxonomy, the taxonomy, evolution and development/synthesis of seed oils, triterpenoid chemistry and evolution, latex products and chemistry (esp. sapota and its chewing gum), northwest and western Native American ethnobotany, the history and development of the naturopathic medicine program and field of study in Oregon, Oriental Medicine, the history of plant use in treating ophthalmologic diseases, Overland (Oregon) Trail “alternative” and herbal medicine, and the chemistry and use of bioengineered products from plants. My short term projects included the development of an updated version of my herbal medicine toxicology database (still in use by an Alternative/Herbal Medicine software program (once again employing the Toxidrome teachings of Howard Mofenson of Long Island, 1980-1990), the investigation of several intoxication cases related to over-the-counter herbal products (adulteration by look-alikes or mistaken identities), research into the local glycyrrhizinate-induced endocrine-like dysfunction cases related to extensive herbal medicine use, the investigation of the tryptophan used by one of three of the first local cases (the result of unmonitored, uncontrolled microbial bioengineering of an OTC by an non-American industry), the study of mushroom grower’s lung disease pertaining to a local Shitake industry, the identification of plants associated with southern Oregon Klamath encampment and a New Mexico ancient tribal settlement, the “chemistry” and geography of local wildfires (i.e. the reasons for the Tillamook burns), and the design and development of a ethnobotany masters program at a local college.

.

In 1987, my lab work on alkaloids, lignans/lignins, simple and complex tannins, flavonoids, seed oils, and coumarins (many Berberidaceae compounds) led me to construct my first extensive chart depicting the evolution of these products in the Plant and Algal Kingdoms, beginning with the “Ranales”, Magnoliidae and certain Rosidae and Dilleniidae herbal medicines with benzylisoquinolines, followed by the rest of the tree over the next few weeks. After three years of alkaloid research, along with teaching the course Chemical In Plants since 1989, I finalized my first written work on this topic in 1992, along with my version of the plant evolution (and chemotaxonomy, natural products, and chemistry) tree, which was subsequently used as top teach my courses given at the university for the next fifteen years (I updated this writing in 2003, copies of which are still found every now and then, and once again, this Evolution of Natural Products/Evolution of Chemicals in Plants book is once again being updated, and given the new technology, more than adequately illustrated. My focus on the evolution of chemicals in plants pretty much pertains to this part of my academic and research history.)

The Evolution of Plant Chemicals

There are reasons plants bear chemicals of medicinal value. These reasons are not as simple as stating there is some sort of combined natural and social darwinian evolution taking place. This argument is very tempting due to its relationship to the highly popular Gaia hypothesis, but it is somewhat an incomplete picture of the phytochemical synthesis process.

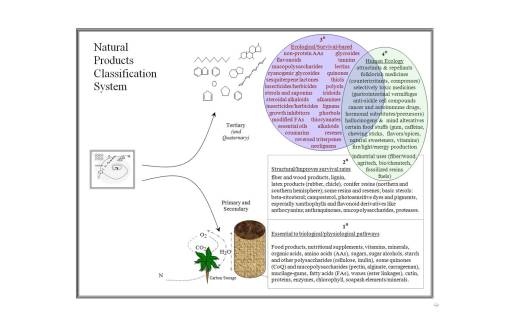

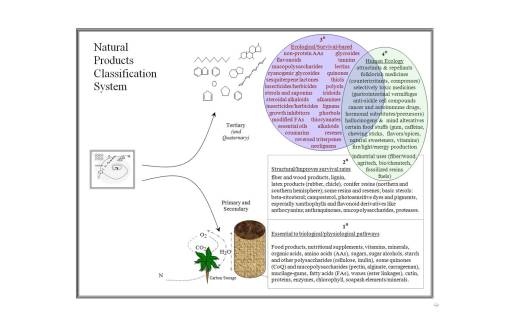

It is best to consider the possibility that there are a number of reasons why plants develop their complex chemistries, reasons that typically have nothing to do with human ecology and the plant. Plants chemicals are traditionally referred to as primary and secondary natural products. The primary products are those essential to the plant living processes, and the secondary products are all those other chemicals plants produce which provide them with additional survival benefits.

To date, the medicinal plant chemist has been quite content with interpreting plant chemicals as primary and secondary products. Whereas many biologists and plant physiologists have become experts in much of the primary metabolic chemical processes (all that stuff we learned in biology, biochemistry, molecular genetics, and physiology classes like the Krebs Cycle, gluconeogenesis, DNA replication, protein synthesis, photosynthesis, the C5 pathway, ad nauseum), and some of the common secondary products such as auxins, gibberellins, xanthophylls, and anthocyanins, to date it has been difficult to accomplish the same with secondary metabolites in plants. Referring to these pathways as secondary metabolites was too simplified for a fairly lengthy and rather complex biological process inherent to all plants.

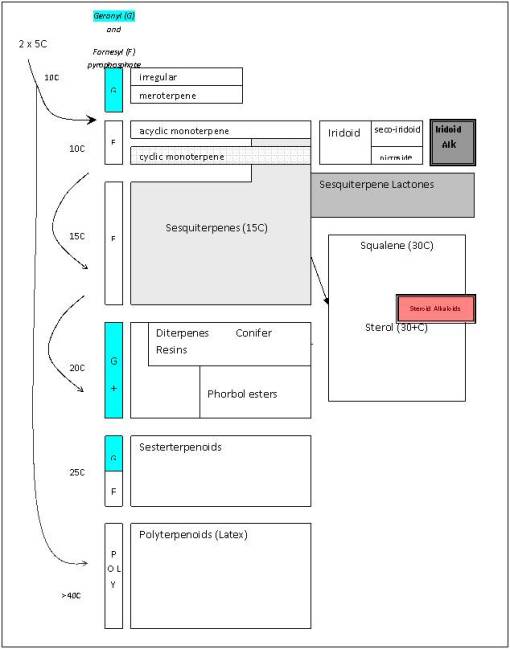

Isoprene/polyterpene paths

In fact, the secondary natural product paths in plants themselves can be broken down in some sort of hierarchical, evolution-derived series of steps taken by plants and their consequences ecologically in terms of survival. This led me to develop a method for analyzing plant evolution, based on levels of importance to plant survival and existence. For example, one way to consider primary metabolites is as a biological “soup” of materials, and the first level of synthesis in plant chemistry as a result of environmental stress, without regard to human involvement–this level of evolution results in the production of chemicals that involve plant to environment interactions or what I call the “environmental soup”. The third level is the ecological level of interaction between plants and other things–these things are biological, and their resulting role is more ecological in nature, I termed this the “ecological soup” of plant chemicals. The final relationship between plant chemicals and other entities in the “anthropological soup” or human nature of plant interaction with their environment. All of these “soups” play important roles in the evolution of plant chemicals. These primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary levels may be defined chemically as follows:

The best way to review secondary natural products in plants is to view their development at three levels.

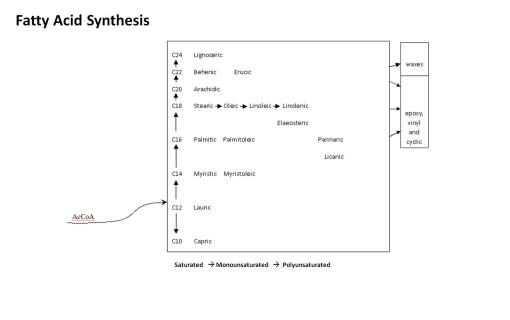

Level 1 products synthesized by plants provide them with an edge when it comes to surviving in their natural setting; these products are the result of massive amount of energy spent producing chemicals that give plants an edge on their closest relatives, or neighbors of their own kind, and are for the most part adaptive to the environment and meant to deal almost completely with environmental features. These are mostly the biological and environmental “soup” products detailed above. Examples of these types of products are wood and fiber chemical groups and the pathways merged to form these entities. They provide protection, enable plants to grow at taller heights, and are usually the result of the plant either slightly modifying or making much larger amounts of substances already produced by their metabolism. When a polysaccharide pathway changes its emphasis from simple starch to mucopolysaccharides, for example, in order to improve water retention in droughtish environments, this is a level 1 secondary metabolite process. When a plant seed oil evolves from small molecular (short chain) form to medium and large (long chain) forms, this is done as a consequence of survival in much colder environments, where short chain fatty acids provide less bioenergy storage, that behaves more like a solid in cold climates, in places where more of this energy has to be stored and has to be more stably transported during the colder times.

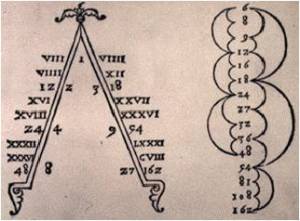

The following is the sequence in oil chemical complexity.

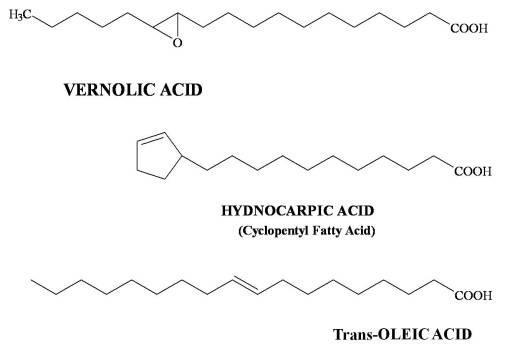

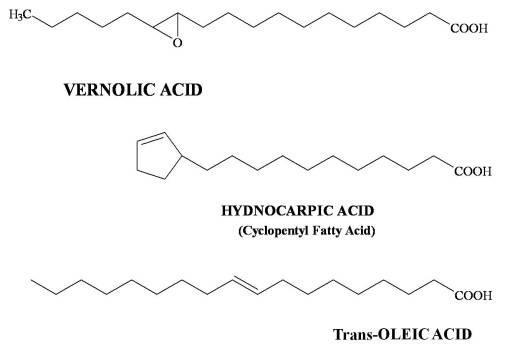

I put a lot of these products at Level 1 because they are essentially common sense in nature. The length of the carbon chain in the fatty acid and the numbers of double and triple bonds is what tells us how evolved the chemical is. Fatty acids tend to evolve from C-12 to longer chains by adding 2-carbon blocks. The early evolved tropical paleoflora (Magnoliidae-Lignosae) predominantly have short chain fatty acids (C12-16) that are saturated. Energy is spent by the plant to make these longer and to produce their double bonds. Those which develop double bonds are more complex. Those which are longer are more complex in an evolutionary sense. Those with very long chains are the most evolved, and often are associated with other species in the family that have other advanced features such a triple bond formation (vinyl fatty acids) and very long chain fatty acids (C20+), for example Asteraceae members and allies. The tropical habitat is often replaced with colder and colder climates as part of this process. Plants adapted to very cold settings produce longer fatty acids with multiple double bonds in order to produce a more stable oil for the temperature changes related to that living environment. Plants heavily adapted at a Level 2 (Tertiary products level) with fatty acids produce fatty acids that serve an ecological-survival purpose, such as the strongly antimicrobial, antifungal gorlic, chaulmoogric and hydnocarpic fatty acids of the Flaucortiaceae (see below). Asteridae members produce cyclic modifications of fatty acids for special needs, i.e. Vernolic Acid.

Level 2 secondary natural products are those that plants produce in order to serve some ecological purpose. These chemicals are produced and directed at other organisms, be they plants or animals. They range from the sesquiterpene lactones and allies developed in some desert plants (used to prevent competitors from thriving in the soil beneath them), to the change in chemistry of a simple sterol making it an effective feeding deterrent effective against slugs and other small herbivores. Flavonoids are a good example of this because for the most part they serve ecological purposes in a plant. There are a few of these that are Level 3 in nature, but for the most part the plant has survived with flavonoids due to their value as petal color-related attractants, as secondary photosynthetic pigments, and in some cases as protectants (rotenoids).

Level 3 secondary natural products are really those which have uses that are invented by man. The chemicals already exist in plants and are probably there for a Level 1 or Level 2 purpose, but this purpose may be related to, or distinctly different from the Level 3 purpose assigned to that chemical evolution by people. The most common examples of these are flavonoids people often cherish as medicinal. The plant doesn’t benefit from reduction in hypertension, for example Hawthorn berry, but certainly man does. The clearest example of an anthropomorphically redefined phytochemical use involves the anticancer drug, which rarely affects animals as much as it benefits man. The epipodophyllotoxin of Libocedrus bark in an ecologic sense is perhaps antifungal, antiviral in nature and therefore protective. To people however it has a toxic effect on cell division and is deadly to mitotic cells, a feature all cells must express to survive, but one that is expressed more frequently by dividing cancer cells making them more susceptible to this form of toxicity.

This method of interpreting plants chemicals give us a better understanding of these natural products and allows for a more comprehensive approach to be taken for understanding how these chemicals in nature and in the presence of different human cultural settings. Once plant chemicals become an important part of human ecology, the long-term impacts of this on the plant species changes. take for example the Level 2 toxins possibly developed to prevent insect and other forms of feeding. These neurotoxic compounds, like nicotine, ephedrine (in Mormon Tea), and perhaps even some of the mood alteratives and hallucinogens like caffeine and mescaline, play one role in nature, and another in the human ecologic setting. Applying this to the seed oil, we see the evolution of short to long chain fatty acids occuring as a consequence of environment, followed by the conversion of these long chain fatty acids into more complex cyclic fatty acids like the chaulmoogric and gorlic acid typical to Flaucortiaceae plants, a substance toxic to certain seed eaters, and important to human health and skin. The erucic fatty found in Cruciferae is non-edible (and toxic) to people, but highly important in industry as a fuel and lubricant oil used in aeronautics; with bioengineering, we modified the oil by reducing significantly this toxic components, resulting in one of the more popular “healthy” cooking oils Canola/TM. As Level 3 compounds, these chemicals, further improve the plant’s chances for survival ecologically, by taking advantage of the much larger human ecology setting; we take advantage of the fact that the plant produces these oils and so make them an important part of our hygienic and medical practices and our various chemical industries.

All plant chemicals have a reason for forming. Scientists once liked to state that the production of secondary compounds was merely a consequence of plants overproducing too many by-products as a consequence of their primary metabolic pathways. The plants had to do something with all those chemical products they produce–why not just assume that plants convert these chemicals into other things, by chance? and if these changes are to their benefit, these plants will just be selected for by nature.

The human experience with plant chemicals provides a very different take on this same situation. Why not allow human ecology to be one of the main reasons plants produce compounds by way of the natural selection process?

In some cases, plants are medicinal due to their natural protective mechanisms, and others some combination of medical and toxicological features. For example when the strongly insecticidal compound nicotine is developed by a plant in order to serve as a natural insecticide. This ecologically-driven reason for nicotine production later gave way to an unanticipated application of nicotine to the human experience. This same argument can be made for the numerous hallucinogens and mood alteratives noted in plants, the various chemicals we have come to appreciate for their utilitarian benefits such as fibers and dyes, and the ultimate end products that come to be following a significant modification of common plant chemicals such as starch, seed oil, latex and cellulose.

Although many plant chemicals in fact have little evidence demonstrating natural ecological reasons for their development, in most cases, there is a reason, only we have not found it. The human experience with plant chemicals and medicines is also an evolution-based production process that a plant engages in; it requires some sort of intervention by man. Other times this unique feature of the plant is due just to the human experience attached to the discovery of that product. It exists regardless of whether or not we intentionally make use of this chemical product. This latter form of evolution of plant use is more an example of culturally-defined evolution of a plant substance than a simply complex example of some natural form of phytochemical evolution we have yet to attach any scientific reasoning for. People appreciate a plant substance for their interpretation of the value of this chemical or chemical-related end product. This often plays the most important role in determining the ultimate value of a plant to a given group of people or sociocultural setting.

Transformation of Common Belief. Significant portions of what we learn in medicine are very much derived from personal and professional belief systems. The philosophy of science is medicine’s religion. Not that science is a bunch of questionably misleading human-defined relationships. There is some value to science and its observations and hypotheses. These help to define the next trail we may perhaps take in our professional career. Philosophy is after all why echinacea is considered an excellent immune agent, right? Those who answer ‘no’ to this usually base their argument for such a claim on the synthesis of data in a laboratory. But the reason the lab experts took on this experimental role in the first place is primarily based on facts produced much earlier when the true plant with this medical use almost went extinct, due to its overharvesting around 1850–the Ratibada of the Great Plains It took a well-disciplined eclectic medicine trained chemist in the early 1900s to prove that Echinacea could perhaps have similar attributes. Which he accomplished, leading to the use of echinacea as the next generation of Ratibada substitutes. It was then up to later herbalists, scientists and doctors to re-explore these early studies, and with the help of money and Occam’s razor, begin their own personal search for “Truth”, a very based way to begin such a study.

Now, a lot of herbalists and plant chemists are not going to like this line of reasoning. It is not intended to say that the study of plant chemistry and medicine has to come to a halt. It is to instead tell readers that the more complex our knowledge is about science and the microcosm or subcellular cosmos, the more likely it is that we can come up with a theory that pleases us about the use s for a particular plant. After all, I spent nearly two decades focused on benzylisoquinoline alkaloids, sesquiterpene lactones, iridoids, fatty acids, colorants, and cancer drugs in the lab. Instead, this is meant to suggest that the history of a claim be fully explored before spending a lot of time and money studying something based on a totally different perspective or philosophy upon which you base your scientific reasoning.

In many cases, new medical treatments are found because they fit a model that is already out there. Instead of allowing some reasonable method of evaluation to guide one to the right compounds foe the cure, we have preconceived notion of what type of chemical group could be something like a cancer remedy. This preconceived notion guides us to find the evidence for an antimitotic we were looking for, or some sort of lectin, or some sort of brand new groups of chemicals in the popular culture of herbal medicine chemistry–the iridoid. Medical botany teachings can be traced from one generation to the next and the philosophy underlying the reasons for effectiveness also traced and its own cultural constructs defined in terms of the period of medical tradition under review. This is not only true for historical botanical medicine, but also many aspects of modern pharmacognosy and contemporary medicine in both the regular and alternative medical worlds. This point of view of medicine places greater emphasis on the mind-body healing processes and any important roles these may play in assisting regular and alternative healers.

My favorite example that I give of this in class is Erasmus’s tale of the Plantain and the Toad, in which the Toad confronts a spider, is bitten on the back and so retreats under the local Plantain leaf. Resting there for a moment, the toad bites the plantain leaf because he/she couldn’t bite the spider. Later, the toad confronts the spider once again and wins the battle.

To Erasmus, this was a folktale of a symbolic nature meant to be retold. So, in the beginning, Erasmus’s story was retold numerous times, in the meanwhile never really being interpreted as having anything to do with medicine and healing. Then one day a herbalist catches wind of this story and slants it is a new direction. The next time this story is retold, the plantain is referred to more as a medicine than any sort of plant cover for the toad. Next this herbalist adds that, somehow, by being in contact with the leaf on its back, the plant was able to heal the swollen spider bite.

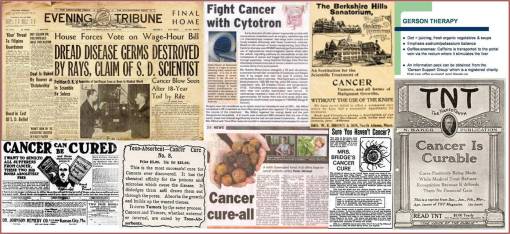

The next time this new version story is retold, it is not just the bite that can be healed with plantain, it is also any kind of swollen tissue. A time or two later this swelling is likened to an abscess, “tumor”, canker or “cancer”, and soon after, with the differences between canker, “cancer” and true cancer not at all well delineated, the plant becomes a “cancer cure”. The result is this Plantain leaf is now being applied as a mash to the surface of skin with a cancer (even though the skin problem was simply a swollen abscess misinterpreted as cancer). Miraculously, this “cancer” goes away, and a new cure for “cancer” is born (the time is now ca 1795-1810). However, during this time there was no way to differentiate true cancer from other “tumors” and “cancers”. And so this legend continues, each time slightly rewritten and paraphrased to best fit the expectations of a writer for the time claiming this to be a “cancer cure “. For example, consider the following case reports from the Botanico-Medical Recorder, Ohio, 1834. It involves the use of a Thomsonian remedy to effectively get rid of “cancer”:

The result of this Thomsonian remedy is obvious: the acidic sorrel ate away at the “cancer”, as it would any wart, abscess, boil, canker, or surface of a “tumor”.

Between 1820 and 1850 (i.e. Wooster Beach and Elias Smith), this story-telling finally hits a number of highly popular medical books, for both regular and reformed medicine. This retelling of the cancer cure story continues into the 1860s when cancer is finally starting to be better understood microscopically and physiologically. Yet the true cure for cancer remains totally misunderstood.

While domestic medicine books are continuing to tout such cancer cures as sorrel, rhubarb and other acidic plants capable of blistering and eroding away flesh more than cure any specific medical problem, the authors of professional writings were beginning to know in better detail the physiological and biological differences between cancer and “cancer” as the public understood it to be. There was however no understanding of cancer as a consequence of cell division. It was still being interpreted as a reaction to various environmental stressors, consisting of what had come to be better understood as an inflammatory response. This complete disconnect between physicians and the general public allowed the discovery of new cancer cures to be founded by a number of popular culture herbalists, gifted healers, and need I say, charlatans in some cases. A good example of this is the founder or renunciator the old-time German born “Essaic” cure (Germans invented it, a nun promoted it: sheep’s sorrel, burdock, slippery elm and turkish rhubarb; read more at Suite101: The Essiac Cure for Cancer http://www.suite101.com/content/the-essiac-cure-for-cancer-pt-1-a261150#ixzz1BNwRmyKy).

About this same time, there was a true cure for cancer already in use out there by many people–podophyllum resin–but that was only being used to treat the liver (Carter’s Little Liver Pills), not the canker or tumor. The true cancer use for the Liver Pills remedy was never known until the mid-1900s, once the mechanisms of DNA and cell division became known It is now the top testicular cancer treatment and is in the small cell lung carcinoma regimen. It wasn’t until we knew what cancer truly was, enough to distinguish it from its similars, that the true cure for cancer could be found.

Continuing with the plantago part of this story, a couple of years ago some scientists who are experts in chemistry finally hear about this miraculous cancer cure Plantago, and without ever double checking the original sources, jump in and initiate some sophisticated chemical and biochemical analyses. Lo-and-behold they find something that could be curing the “cancer” after all–one says it is a flavonoid, another claims it to be an iridoid, the third individual a Proteinase enzyme. Either could be right with what they stated–if the plantain worked and was originally used to treat a cancer on the toad’s back. But it wasn’t.

The result of this type of query by scientists is what has come to be knnown as the Occam’s razor effect. They both got the results they were hoping to get, without concern for re-evaluating the origins of this tale once the discovery is made and published. Since the common belief is there, it had to be true . Since it is a very old tale, that was told and retold, they wonder-how could it possibly be wrong?

Now, plantain is by no means the only example of occam’s razor in plant chemistry and medicine. Transformation of common belief (TOCB) is what makes plant medicine what it is today. Very few of the current claims about plant medicines have both experiential and scientific validity.

The first examples I uncovered of this phenomenon in plant medicine history related to the Native American snakebite cures common to early American medicine. This is such a common philosophy in medicine that in the mid-1990s I began exploring its origins. I found evidence for this philosophy in the earliest colonial and exploration writings, and in the Oregon Trail writings I had commenced in 1993. I also noticed that there was some changes in the wording about the uses of these drugs by herbalists, to keep up with the industry for the times. By doing so, they transformed the remedy and how it works from one condition to another. For example, the snakeroot used to treat convulsions induced by snakebites might be turned into a seizure remedy (Scutellaria), another snakeroot was transformed from a remedy used to treat muscular pain induced by venom to a remedy used to calm uterine smooth muscle contractions (menstrual pains) (Caulophyllum). Since skeletal muscle and smooth muscle are totally different in their pharmacology, I realized there was something interesting going on here. People redefined a herb’s use and then tested it, believing in their own claims, they increased the likelihood that they would meet their own expectations and produce the outcomes they needed.

Now, when science looks back at many of these uses, scientists accomplish this according to their standards and little more. With herbal medicine, there are numerous interpretations about medicinal plant use which we are informed of by historians, anthropologists, herbalists, botanists, chemists, pharmacologists, physicians, naturopaths. This is much like the blind man describing the elephant story of Buddhist canon Udana 68-69:

Now, when science looks back at many of these uses, scientists accomplish this according to their standards and little more. With herbal medicine, there are numerous interpretations about medicinal plant use which we are informed of by historians, anthropologists, herbalists, botanists, chemists, pharmacologists, physicians, naturopaths. This is much like the blind man describing the elephant story of Buddhist canon Udana 68-69:

“”Thereupon the men who were presented with the head answered, ‘Sire, an elephant is like a pot.’ And the men who had observed the ear replied, ‘An elephant is like a winnowing basket.’ Those who had been presented with a tusk said it was a ploughshare. Those who knew only the trunk said it was a plough; others said the body was a grainery; the foot, a pillar; the back, a mortar; the tail, a pestle, the tuft of the tail, a brush.”

Or better yet, retold as:

“Thereupon the men who were presented with the first chemical separation answered, ‘Sire, the cancer remedy is a cellulose fiber.’ And the men who had observed the second separation replied, ‘Ah, the cancer remedy is like a polysaccharide muciloid.’ Those who had been presented with the third extraction said it was the pigment chlorophyll. Those who knew only the fourth said it was a phytosterol; others with separate extractions said the cancer drug was an alkaloid hard to separate out, yet another the iridoid aucubin, and for others: a tannin, the leaf’s wax cutin, an immunogenic complex polysaccharide found just in the mesophyll, an unusual lectin contained by just a few cells, and finally the enzyme protease. Ad nauseum.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Blind_men_and_an_elephant

The lesson here: Occam’s razor brings forth the cure.

A chemist can look at any plant and have so many different types of chemicals to be found and classified, that one of these could be the real thing, or not. It depends upon what we want to believe. To one physicist, light is a wave, to another in the same lab on the same, just a few seconds later, that same light is a particle (the wave-particle duality theory, see http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wave%E2%80%93particle_duality). To one scientist, this was a matter of fact, to another, the results of an individual’s perception of things.

ENVIRONMENTAL RESEARCH – PART 2 — GEOGRAPHIC INFORMATION SYSTEMS

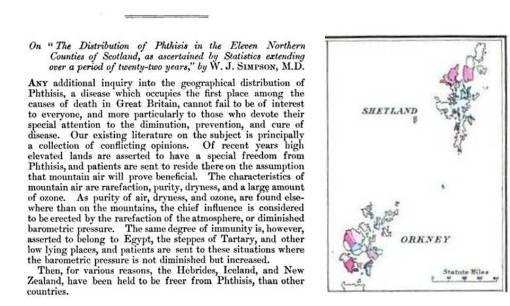

Three things led me to my work as an epidemiologist from 2000 on. I began to map plant distributions to document the relationships between different natural product types around the world. These relationships were in part due to the massive shifts of continents that took place due to the tectonic plates history of the earth. I used this to better understand how oils were evolved relative to climate patterns and latitudinal orientation of the major plant groups. This also helped define how and when certain chemical compounds became an advantage to their survival, such as the evolution of steroids and saponins due to their anti-feedant effects upon invertebrates with moist skin (worms and snails). The reasons for the early evolution of toxic amino acid by-products such as nicotine and ephedrine were obvious in terms of plant evolution. The same could be said for the reasons plants developed such things as tannins, polyphenolics and lignins.

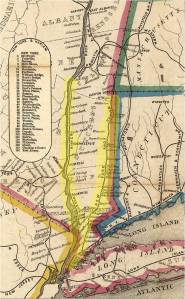

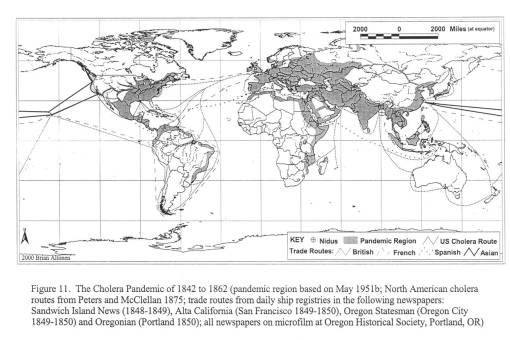

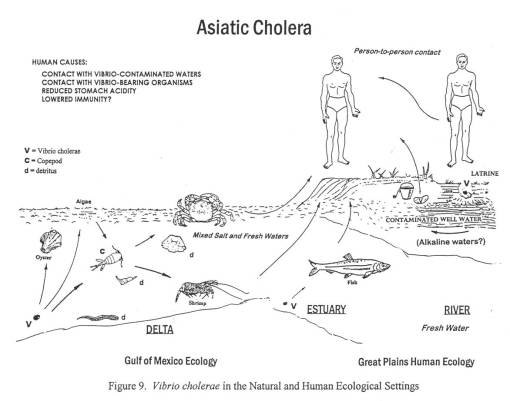

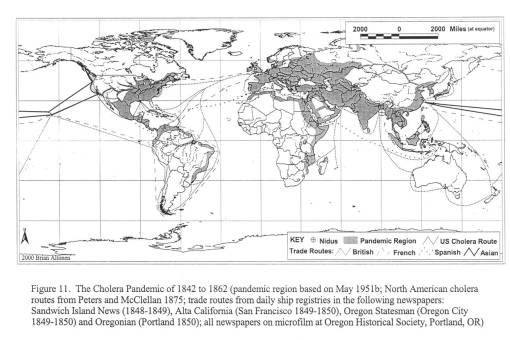

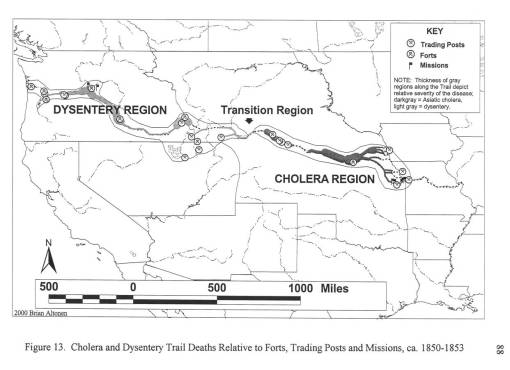

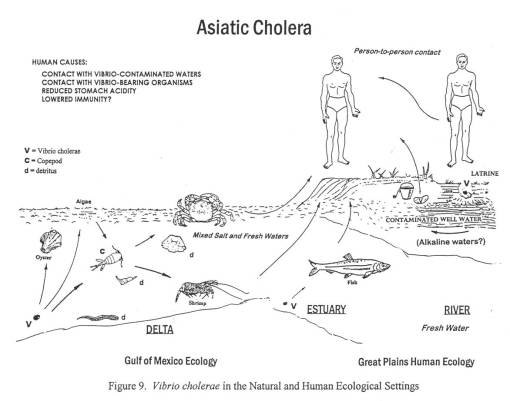

I next began to develop a way to map out the distributions of medicinal plants in general, more for teaching reasons, and digitized a version of my chemotaxonomy tree for use in ArcView GIS fairly early in my years using this software. At some point, while plotting out Great Plains flora, I came upon repeated articles mentioning the uses of plants along the trail for medicines. Often times, the primary disease was “cholera.” When I noticed that a number of dysentery epidemics were mistaken as asiatic cholera from Wyoming westward, I decided to research this topic and determine a way to identify that mysterious form of diarrhea hitting the overlanders. And so my more serious work with GIS and remote sensing began.

Cholera on the Oregon trail, 1849 – 1854.

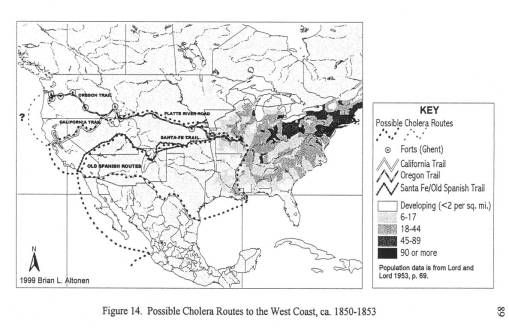

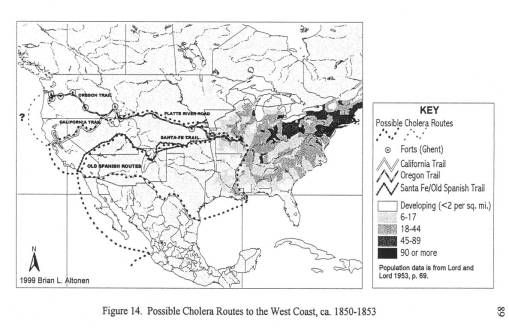

For my first graduate degree, an MS in Geography, my thesis was informally known as the “geography of diarrhea.” More professionally stated, my work for the thesis focused on the various environmental human features responsible for two epidemics that struck the Oregon Trail between 1849 and 1854. These epidemics were pretty much a recurring feature in Oregon Trail history, with some years worse than others.

The first epidemic of diarrhea in eastern Nebraska was due to recently slaughtered Bison found near an Pawnee Indian camp. Local history tells us that these 1845 to 1847 notes of “cholera” were closely associated with the dead Bison seen as the Platte River bends southward along the trail and the emigrants travelled westward. These dead bison were due mostly to a recent uprise that had taken place between local Sioux and Pawnee indians disputing this territory. By passing these carcasses, travellers commonly suffered a severe spell of diarrhea, which they attributed to the bad water and the bad meat they obtained by hunting in this region.

The second much larger epidemic of diarrhea in Nebraska was due to the Asiatic Cholera global epidemic striking the midwest. This epidemic made its way inland from New Orleans to St. Louis to Fort Kearney, between March or April of 1849 and July of 1849. Travelling to and from the fort was done by water, land and foot. Most likely, it was the occasional supply ships that first brought this form of cholera to the Fort, followed by individuals infected at their jump-off towns and in St. Louis during the later months and years.

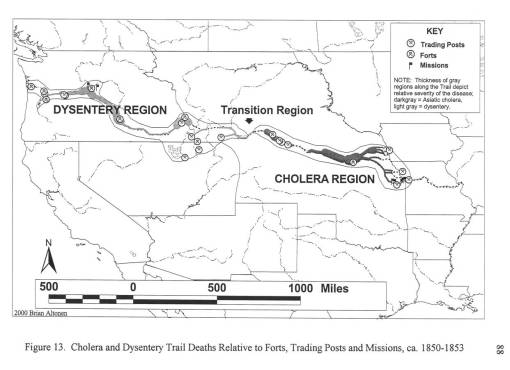

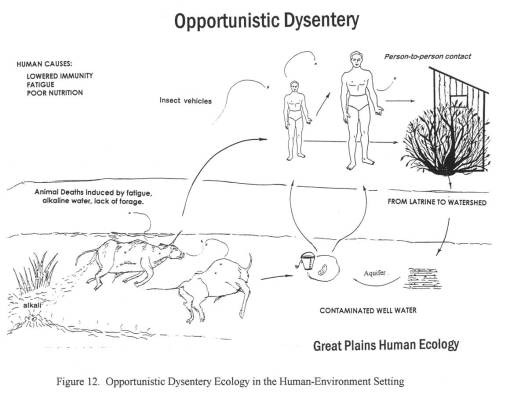

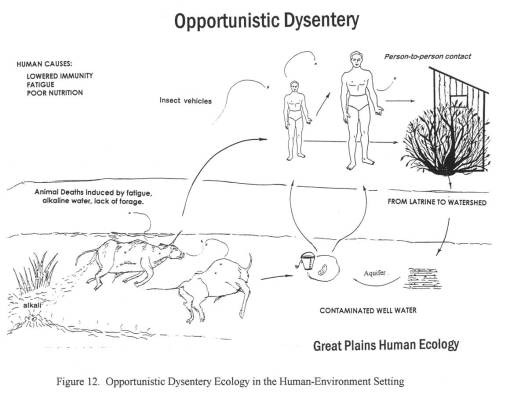

The third diarrhea epidemic, akin to the first, resurfaced in eastern Oregon around mid-summer 1852 and finally hit Portland by January of 1853. This epidemic was due to an outbreak of an opportunistic form of dysentery caused most likely by the Salmonella intermedia released by decaying animal flesh lying between Wyoming and the Idaho-Oregon border. Although other bacteria may be associated with decaying animal flesh, the most ubiquitous bacterium with the best ability to produce the “western cholera” as it was descibed in the diaries, was this particular type of salmonella.

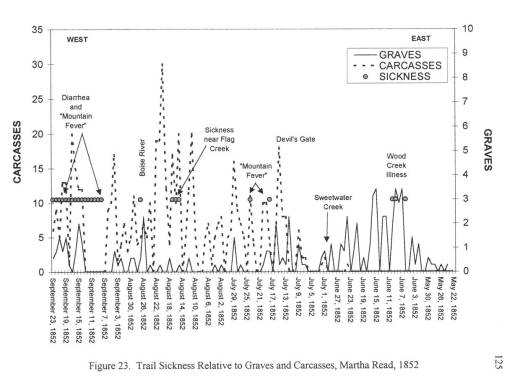

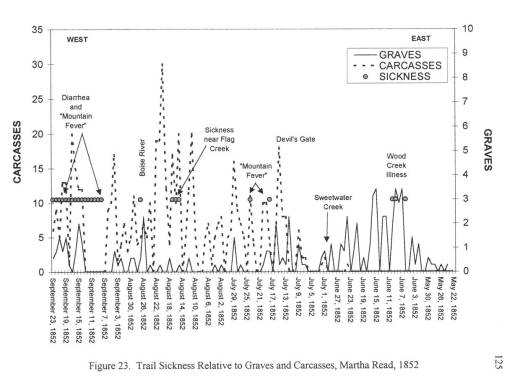

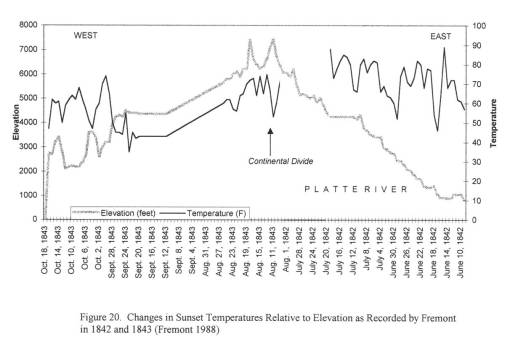

By mapping each of these epidemics, it was demonstrated that human population features were responsible for the asiatic cholera suffered during the first few days of travel along the trail; this epidemic was often fatal. The pre-1849 outbreaks and the second set of 1849 to 1854 outbreaks of diarrhea were due to dead animals. In particular, durign the years of heavy migration (1851 to 1853), we find the effects of animal carcasses on overlanders beginning to reach their peak. The most likely cause for these animal deaths, namely oxen, during these migrations was the topography of the region and constant, recurring and tiring elevation changes. Due to this part of the migration, one physician noted passing hundred of carcasses per day in Wyoming, mostly in the foot hills region of this part of the migration. From central Wyoming westward, the most common causes for diarrhea remained exposure to these dead animals.

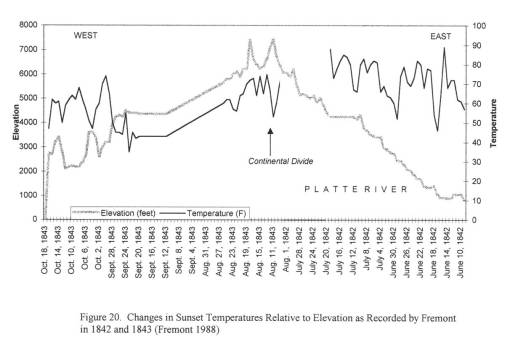

Important climate data was obtained from Fort records for this time, since weather records had to be kept for health-related purposes by all government operated military forts. The best elevation-temperature data on travelling the trail came from explorer and government official John Fremont, who travelled through this region in 1852 and 1853; he kept temperature, weather, and barometric pressure records which were taken several times per day. Due to the details of his record keeping in the journal, his entire travel route and places of encampment could be mapped. Much the same could be said for another official travelling to Oregon in 1845, whose diaries also made important notes on the local ecology, geology and water-related features.

The best insights into these two diarrhea epidemics came from the trail diaries many people kept, especially those written by physicians or scientists, and women trained in the new field of medicine known as hydropathy. The physicians kept daily weather logs and medical notes on their excursions. Hydropaths kept track of the weather, the number of dead horses and oxen passed each day, water sanitation, diet/food behaviors, and human and animal sanitation-related behaviors and practices. This enabled me to determine where the causes for each case of diarrhea arose–where the disease was most likely first contacted, followed by where and when it was transmitted by the various people and animal hosts involved in this process.

Other forms of diarrheas such as “flux” due to mineral springs/saltwater contact and drinking and the possible contamination of meat-related food sources were evaluated. The first was ruled out for the most part. Some trail springs were consdiered medicinal, but most were considered deadly and therefore not imbibed.

A possible source for contaminated foods causing diarrhea was uncovered for the fort in western Wyoming, just before the southwestward pass into Utah. This “Sioux trading post” as it was called provided travellers with food supplies, including self-produced dried meats. After that, a “Fort” run by an individual also provided a source for contaminated meats leading to diarrhea. A third location, a fort in Idaho, was unlikely to be the direct cause for the diarrhea that soon followed after passing by its walls; this fort had another problem related to the pile up of dead horse and oxen carcasses outside the fort itself, by a nearby water source.

This project also required that I review the geography of another vector-borne trail disease–Rocky Mountain Spotted Fever (referred to by some as some form or Mountain fever linked to the Dysentery, the bloody diarrhea also experienced at that time). Typically transmitted by insecta infected by this organism through local deer populations, this disease has its own signs and symptoms, which for the most part lack any similarities with any of the diarheal epidemics reviewed. In short time, it was determined that this Mountain Fever was an incidental fever experienced by those also infected by Salmonella intermedia.

Also ruled out and researched for this study are the geography and epidemiological behaviors of Giardia, Listeria, Entamoeba (the cause for true dysentery) and even E. coli.

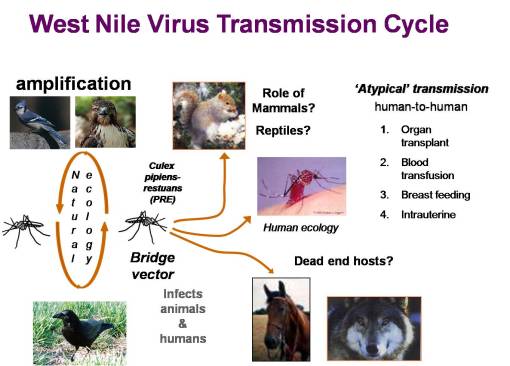

The Ecology of West Nile.

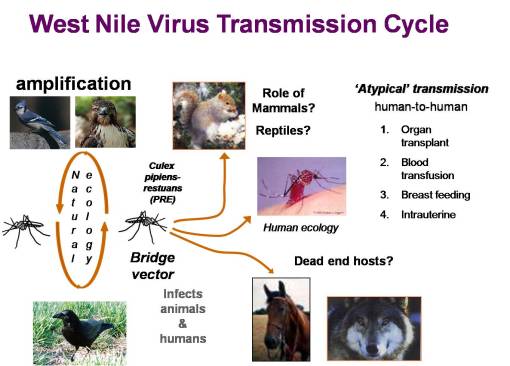

In 1999, the possibility of West Nile making its way to the US hit the news in the New York Times. This started me thinking about my experiences in the Hudson Valley as a child, the area where many of the dead crows associated with West Nile were being found. During my childhood in New York, I was very much a woodlands-bound boy, and knew all the streams, swamps, and glacial ice melt ponds in the county where I was raised. In 2000, I did some research on mosquito mapping, but focused mostly of two other public health matters popular for the time–cancer due to environmental causes and lyme disease due to tick-rodent ecology.

Both of these GIS epidemiology projects were supported by grants provided to me by several local agencies and one regional agency. The lyme disease research focused on the ecology of Lyme, Connecticut and the Hudson Valley where the disease managed to spread most rapidly, and the southern Oregon-northern California region where it was rapidly developing on the west coast. This work focused on host-vector ecology studies and resulted in my discovery of a natural border to lyme disease migration in southern Oregon–a chrysolithic soil region where the flora were non-supportive of the organism responsible for borellia disease, due to its host (rodents) behaviors and feeding needs and the impact of local flora and lizard populations on borrelia vitality (a local lizard has a natural defense against borrelia, and can carry it but prevent its passage to new hosts).

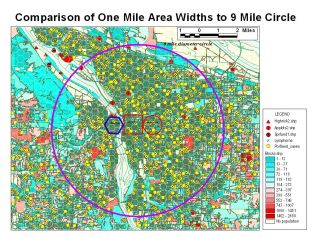

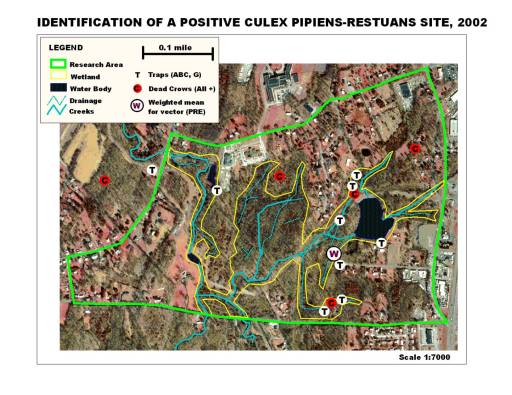

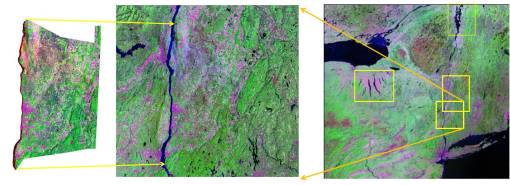

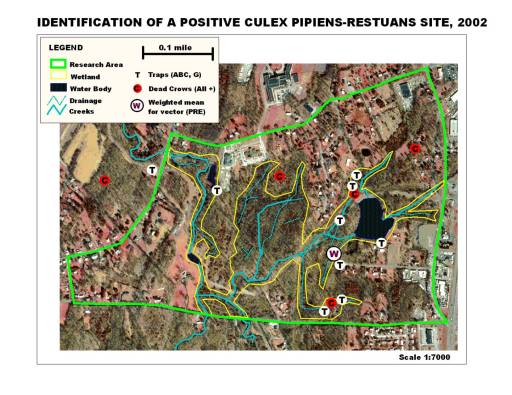

This told me that phytoecology/phytogeography played an important role in disease ecology, at an organismal level typically not-evaluated by disease ecologists. In 2002, when I made my way to New York, my first job in public health dealt with the local west nile fever problem now going at full pace. During my first season exploring this problem, I simply watched the disease and host-vector behaviors as they took place over the year. The following season, I inventoried all the data accumulated on the mosquito trapping that had been done since about 2000, and the various field observations made on mosquito larvae populations for the entire county. Once the data was tallied up, some temporal and location (ecologic) summaries could be proposed in relation to known causes for west nile and its particular mosquito species vectors to infect animals and people. In mid-2003, this enabled me to survey and develop detailed descriptions of all trapping and dead animal pick-up sites, leading to the development of a way to model mosquito behavior in relation to local land use, physiographic, topographic, phytogeographic, and hydrogeographic features. By July 2003, this enabled me to identify the first nidus or nest for positive testing west nile carriers in the county, through centroid analysis developed from the 3 positive testing crows just documented, species data pertaining to traps in the immediate region, and local ecologic studies.

Throughout the remaining season, I developed and tested a way to perform transect studies of various types of regions to map out biodiversity and vector-related behaviors in relation to stream and flood plains geography, mountain edge elevation change, and phytoecology species richness and biodiversity features. I then added to this GIS work my experience with the use of National Landuse Classification Data (NLCD) digitized grid maps, Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) raster maps, and aerial photographs. Small area analysis was performed around several sites with positive testing human cases and infected animal hosts. Mosquito species diversity in relation to species richness and biodiversity were statistically analyzed. Several major rivers/creeks were compared in terms of species distribution in relation to topography, landuse and human population density features. 60 miles of Hudson River shoreline was mapped for vector species to determine how species were distributed relative to river edge and whether or not the estuary itself had its own vector species ecology related to other brackish water west nile hosts noted in that state (paired shoreline and inland traps were set approximately every five miles or less). The GIS was used to document the source for a swarm of a nuisance species–a local sewage treatment center with sewage upwelling, release and a 20×50′ area of of notable ground-surface spillage.

For Conference information and rewards received for this West Nile work see:

http://www.esri.com/library/newsletters/healthygis/healthygis-spring07.pdf

http://www.directionsmag.com/pressreleases/gis-users-excel-in-communication-service-and-vision-for-health-and-human-se/110759

http://www.gpsworld.com/gis/gis-and-mapping/news/esri-lauds-winners-2006-communication-service-and-vision-awards-7688

http://www.geoinformatics.com/blog/latest-news/esri-honors-award-winning-health-gis-programs-and-projects

http://www.gisdevelopment.net/news/viewn.asp?id=GIS:N_wkqbixdrmu&cat=New%20Products&sub=GIS