QUOTE: “A report calls CDC’s commitment to lab safety “inconsistent and insufficient.” The report also says “laboratory safety training is inadequate.””

A reminder that respect from the public is also very important. These are the events from this past year which were preventable (even if just in an ideological sense). They should be used to define the goals for the up-coming year. Notice that two quality of care related needs have been included (limited coverage by SES, and ethnicity/race).

Source: edition.cnn.com

A good reminder of how we got this way is to simply look back at the past year’s events. Since March 2014, we have had several global disease outbreaks or concerns arise in the news, about 1/5th of which really could have been managed better–the rest are status quo for surprising outbreaks and such. This 20% that weren’t well handled have "issues", we can call it, with poor management and preventive health practices. Another 10-20% also have public health related medical practice problems, that are the consequence of mistakes made at the clinical level, by provider or management and administration. But the bulk of medical emergencies do have a certain amount of unpredictably that make them hard to predict will emerge–hard to prepare for.

But once the signs of a problem are there, those 20% (or maybe 30%) of events we could have taken preparatory action for, should have been managed professionally and quickly in due time.

The problems arise when we don’t respond to an emergency in time. The fact that this in the past years has involved several kinds of emergencies, tells us the system is in really deep trouble. Now if we add to this our poor responses to natural disasters, there is much more to complain about, and god forbid, should another 9-11 event happen, odds are we will not respond any better to this disaster as we did to the prior.

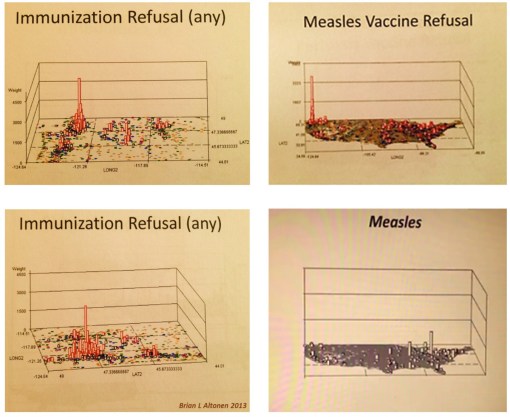

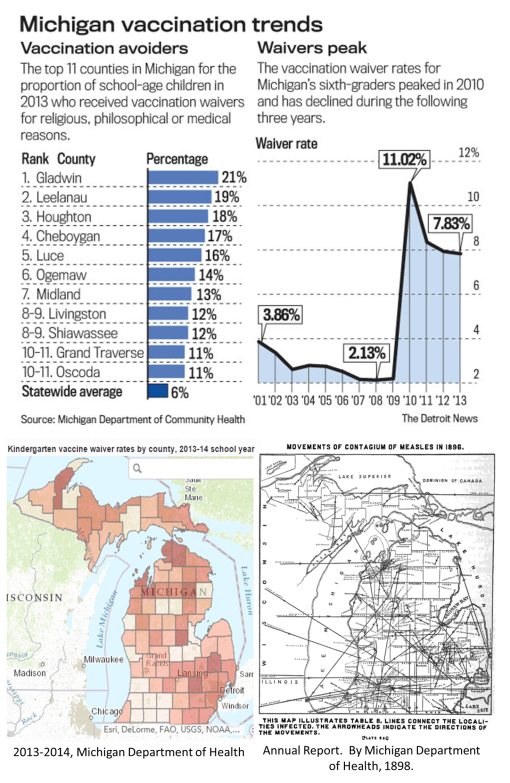

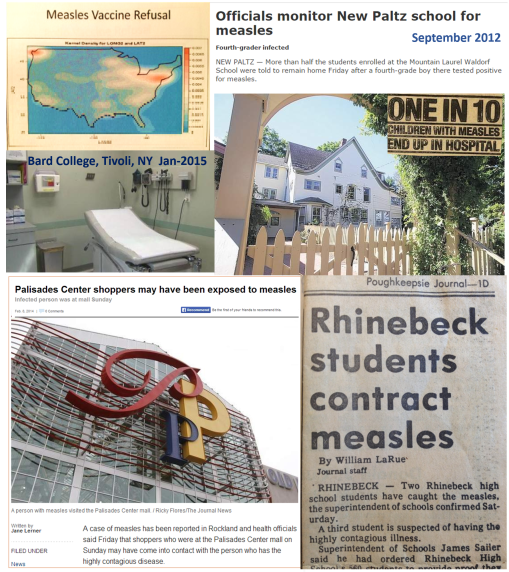

October 2013 (the cases of measles that struck the Palisades Mall in Hudson Valley NY) gave us the warning we needed to be prepared for the 2014 Measles outbreak via Disneyland. My April 2014 posting noted our lack of preparedness in this matter (need I say, living in close proximity to the 2013 outbreak, I have the right to know and experience needed to realize the dilemma we are in.)

The medical field itself knew it was not ready in May 2014, before the famed 2014 outbreak, it was realized that "Measles is making a comeback." [The Disney outbreak initiated in December 2014.]

The border crisis with people coming into this country caused some hype, in June; that too became true and is the reason Disneyland could be so successfully infected.

But these are not the main concern with this posting. The main concern here boils down to one thing–poor management and leadership. Safety procedures are not abided by at CDC. Record keeping was historically poor, and so we are still finding those old 1950s vials of small pox we put away for the moment, perhaps to send later to some biosecurity/bioterrorism storage facility. Imagine what might have happen had that rubbish made it to the landfills instead of the incinerator, by a third party company hired to clean out the building for renovation or leveling.

Technology wise, the public masses are better informed that the leaders. I know that childhood diseases can spread because of what I saw in my neighborhood for twenty years in the Pacific Northwest, after talking openly with neighbors who weren’t on any health insurance (even MCD), and who refused to immunize their children. The fact that Bot users knew about Ebola before other in WHO or healthcare is a scary finding–it’s like having to rely upon your ham radios more than your TV or regular battery-run AM/FM radio during the cold war era. If I were a survivalist, I would interpret this as a sign to invest in a new multifaceted high tech shortwave communicator.

The medical world in general has been lazy about some technology. GIS is one of the best examples of this. It is heavily used by national programs, for internal reasons only. Theoretically it has epidemiological, preventive care use, but is rarely employed by experts for meeting such needs. We know this because neither the spatial diffusion prediction models nor ecological models for what Ebola was have rarely been mentioned or published with much determination. Even more, as always, this technology is used mostly as a retrospective tool; not a preventive tool. Could the flight of Ebola positive cases to Houston, to New York, where ever, been prevented? It’s easy to say no, not having developed a system to base your decisions upon. The Middle Eastern respiratory Infection and Chikunkunya could not have been predicted for their outbreaks. The latter could have been ecologically assessed more thoroughly and successfully. Makes you wonder which ones (zoonotics) are going to arrive in 2015, the some tick disease, or perhaps a south american encephalitis, or perhaps Bos Tb infecting our cattle? Like the one article states: "Mapping could help stop ____ spread", if it were engaged by the right experts.

Our concerns about polio are too few. We use the Herd Theory as the reason for this. But disease regression is happening apparently; if the herd theory continues to fall apart as a useful paradigm, we’ll need to address once more the return of poliomyelitis (but there are still several more countries that have to be penetrated first by it).

Because we have done little to deal with ethnicity differences in health, and poverty related differences, we do have even worse issues to contend with in upcoming years. Cultural emergence in the US is going to make some diagnoses and diseases become more prominent, be they of an infectious or physical/ physiological nature (culturally-link cardiac abnormalities, genetics diagnoses, etc.) , or of a cultural philosophy and behavioral cause (infibulation, culturally-bound syndromes).

These are not so much directly CDC related–CDC cannot regulate the in-migration of people who believe is some of these controversial behaviors and practices.

But CDC can oversee and regulate its own workers and their fellow workers in the health care field more efficiently–like teaching MDs not to be so self-egotistical about the improbability that they could cause the next epidemic, by allowing a patient to not be treated, or refusing to place their own self into CDC-recommended quarantine. Common sense is apparently not a physician’s (or nurse’s) primary skillset.

In the end, we must link these problems to managers and directors. Of course, the president or CEO is often who we try to blame and expel. But that individual alone is not the cause.

Rewriting the rules does not eliminate the problems. Having a committee developed to oversee past behaviors and uncover the mistakes will not suffice. Ultimately, leadership has to change for this program to get better. Then the policies need to be rewritten. Finally, the right skilled individuals need to be hired, so the agencies can catch up on their IT skills, especially the ones they cannot employ that well, for the moment.

See on Scoop.it – Episurveillance