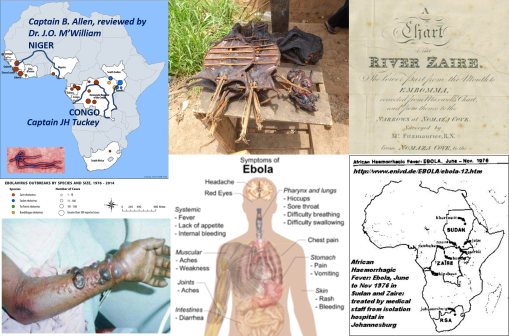

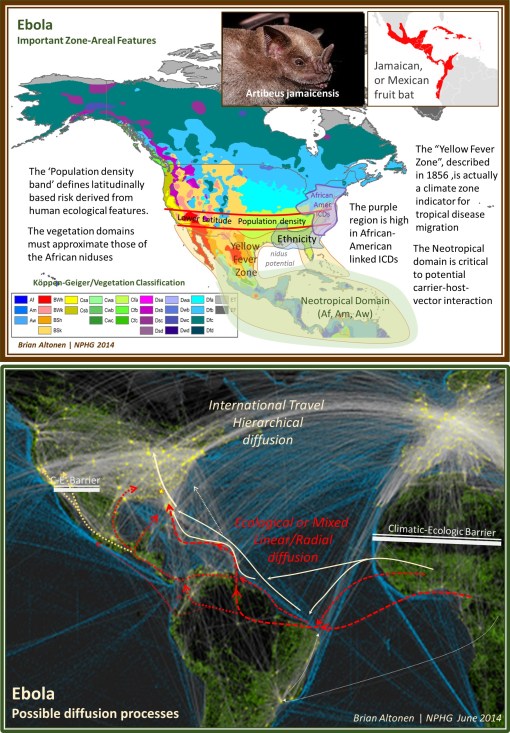

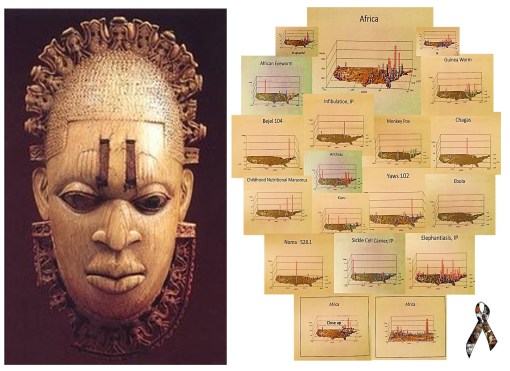

There are two important historical epidemics to note that are very similar to Ebola. The first took place in 1816 along the Zaire/Conga River. The second along the Niger River where it connects with Tschadda. These are both epidemics that began with fever outbreaks, but which led to a high fatality rate and had symptoms that demonstrate a unique form of internal organs deterioration that other fever epidemics do not normally present with. Fewer cases demonstrated the internal blood mass formations seen in the more contemporary outbreaks. The most resemblance between these two outbreaks are their dates of initiation, days until fever symptoms, speed of spread to their others in the teams, and time until death. Both were also colloquially termed “River Fever” These support my premise that the Ebola and some similar diseases have been around since they were first noted by the Portuguese missionaries in the 1690s. Both of these overlap with the geographic distribution that we currently are familiar with, and are consistent with the topography, ecology and human population features determining how this disease may be spread.

In a related posting, I provided the map depicting German medical cartographer Friedrich Schnurrer’s interpretation of what he learned about the Congo River epidemic documented by a Portuguese missionary leader Fr. Anton Zuchelli (1696). (see https://brianaltonenmph.com/2014/10/14/is-there-an-early-history-for-ebola-preliminary-review-says-yes/ )

The following are the notes contained in reviews of the two writings pertaining to the above mentioned Ebola-like experiences.

CAPTAIN JAMES HINGSTON TUCKEY, 1816

The first is regarding the September to October 1816 Congo or African Fever epidemic experienced by Captain James Hingston [Kingston] Tuckey:

[QUOTE]

“The crew consisted of eight petty officers, six artificers, fourteen able seamen, a serjeant, a corporal and twelve privates of marines making in all fifty six persons, of whom twenty one were doomed never to return. ‘Never’, says the editor, ‘was an expedition of discovery sent out with more flattering hopes of success, yet, by a fatality almost inexplicable, never were the results of an expedition more melancholy and disastrous.’ Captain Tuckey Lieutenant Hawkey Mr Eyre (purser) and ten (eleven) of the Congo’s crew — Professor Smith, Mr Cranch, Mr Tudor, and Mr Galwey, (a volunteer), in all eighteen persons, died in the short space of three months! Two had died in the passage outwards and the serjeant of marines survived only till the vessels reached Bahia.”

[END QUOTE]

Note: Captain Tuckey was taken ill September 17, died October 4, 1816.

Source: Art IV. Narrative of an Expedition to explore the River Zaire usually called the Congo in South Africa in 1816 under the Direction of Captain JH Tuckey . . . to which are added, the Journal of Professor Smith, some General Observations on the Country and its Inhabitants, and an Appendix containing the Natural History of that Part of the Kingdom of Congo through which the Zaire flows. Published by permission of the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty 4to London 1818. Book review in ‘The Quarterly review (London)’, January 1818. See http://books.google.com/books?id=y3i1-YybvCAC&pg=PA335

***************************************************

CAPTAIN B. ALLEN, 1841

This is regarding the Deaths from September to October 1841, at the confluence of the Niger and Tchadda, where Captain B. Allen and the crew were heavily infected, one third deceased, reviewed by Dr. J.O. McWilliam [M’William].

[QUOTE]

“Of the one hundred and forty five white men, only fifteen escaped the river fever; while of the one hundred and fifty-eight blacks, only eleven were attacked. The number of deaths is not clearly shown; but what from fever and other casualties, the tables appended show a total of fifty-three, among whom were Captain B. Allen, Lieutenant Stenhouse, Dr. Vogel, Mr. Kingdon, Mr. Willie. Mr. Wilmett, and two of the assistant surgeons.”

[END QUOTE]

Source: Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal, Volume 12, Sept. 9, 1843.

http://books.google.com/books?id=G7MaAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA265

(Note: this Ebola is not as deadly as the current).

For the next several years, “Niger Fever” was a terms used to defines these unique cases presenting along the Niger. Eleven major publications refer to this term for the diagnosis,, including The Lancet, British and Foreign Medical Review or Quarterly, Medico-Chirurgical review, and Edinburgh Med Surg Jl. It is also contained in Robley Dunglison’s 185 Medical Lexicon. See also John Forbes (ed.) book review in Brit. For. Med. Rev. Q., July 1843, at http://books.google.com/books?id=B_AEAAAAQAAJ&pg=PA259 😉

Supporting documents for these fevers being quite different from yellow fever, malaria, and numerous other more common fevers are contained in McWilliam’s Autopsy notes, details of which were published in his book and as part of the combined book review found in the Edinburgh Med. Surg Jl., 1845, v 63). Link: http://books.google.com/books?id=t_8aAQAAMAAJ&pg=PA432 ; another version http://books.google.com/books?id=-Vo9AQAAMAAJ&pg=PA392

See on Scoop.it – Medical GIS Guide